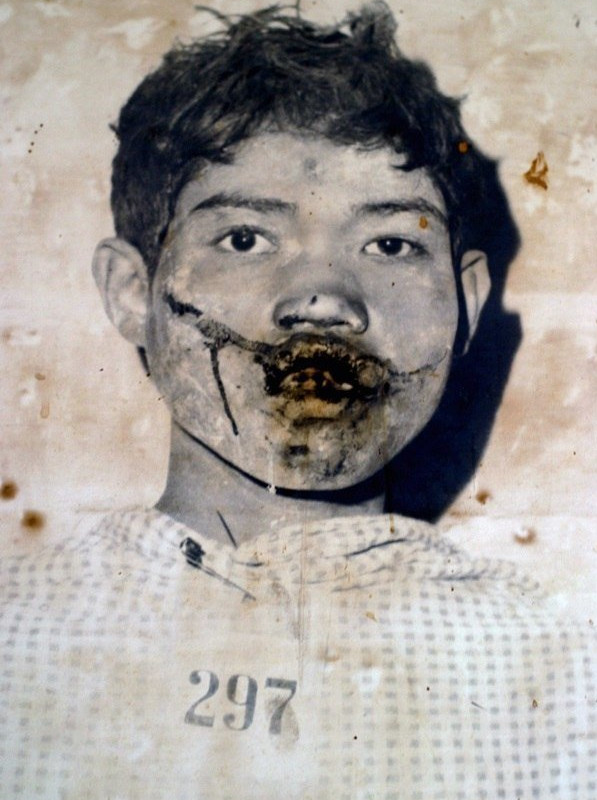

Prisoners of Security Prison 21, Tuol Sleng suffered “beating with fists, feet, sticks or electric wire; burning with cigarettes; electric shocks; being forced to eat faeces; jabbing with needles; ripping out fingernails; suffocation with plastic bags; water boarding; and being covered with centipedes and scorpions”.

Cambodia

The Cambodian genocide was the systematic persecution and killing of Cambodians by the Khmer Rouge under the leadership of Pol Pot, who radically pushed Cambodia towards communism. It resulted in the deaths of 1.5 to 2 million people from 1975 to 1979, nearly a quarter of Cambodia's 1975 population.

- Pol Pot

- Democratic Kampuchea

- Genocide

- Party of Democratic Kampuchea

- National Army of Democratic Kampuchea

- Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea

- Justice / Punishment

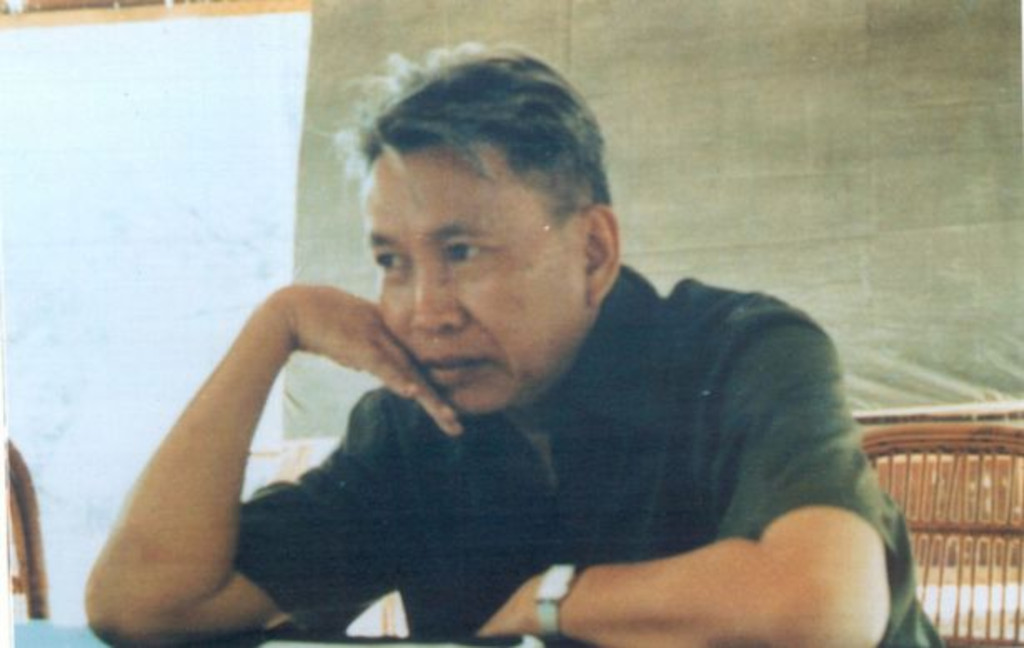

Pol Pot

Pol Pot, born Saloth Sar led the Khmer Rouge from 1963 until 1997. Sar left attended the École Miche, a Catholic school in Phnom Penh. Later in Paris, Sar was exposed to anti-colonial, revolutionary, and socialist ideas. He became increasingly radical, outraged by French colonialism. Thus Sar became a founding member of the Khmer Rouge, a party dedicated to socialist revolution in Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge’s ideology combined elements of Marxism with an extreme version of Khmer nationalism and xenophobia.

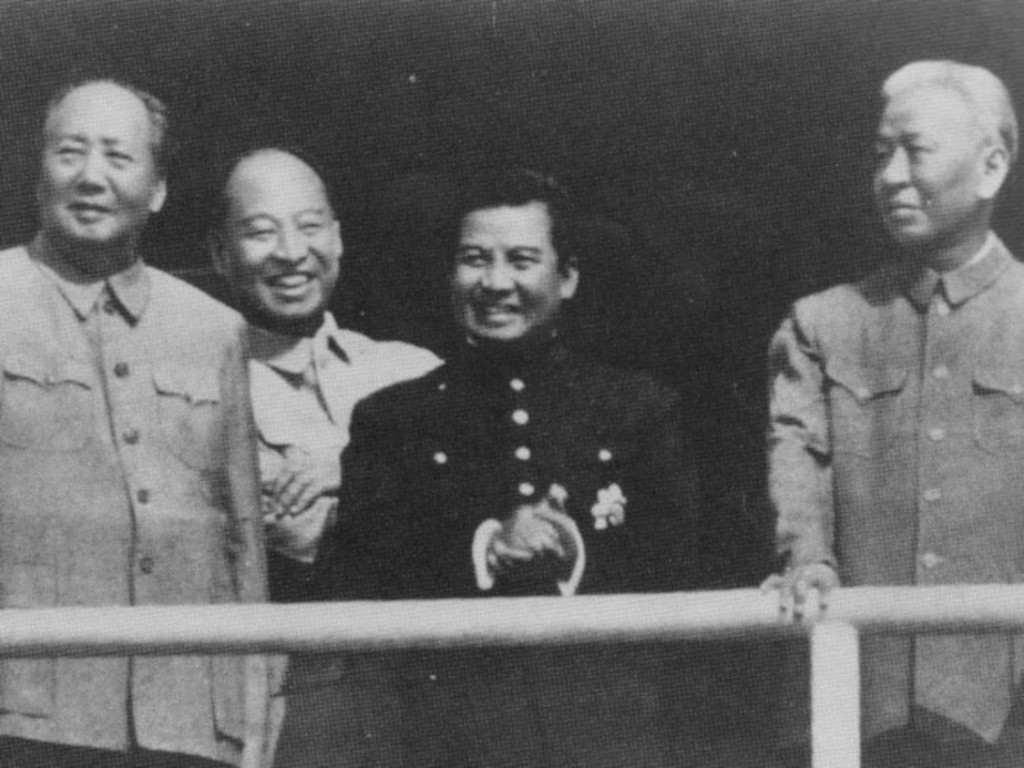

Pol Pot and Khmer Rouge had long been supported by the Communist Party of China (CPC) and Mao Zedong; it is estimated that at least 90% of the foreign aid to Khmer Rouge came from China, with 1975 alone seeing at least US$1 billion in interest-free economic and military aid from China. After seizing power in April 1975, the Khmer Rouge wanted to turn the country into a socialist agrarian republic, founded on the policies of ultra-Maoism and influenced by the Cultural Revolution.

Pol Pot and other Khmer Rouge officials met with Mao in Beijing in June 1975, receiving approval and advice, while high-ranking CPC officials such as Zhang Chunqiao later visited Cambodia to offer help. To fulfil its goals, the Khmer Rouge emptied the cities and forced Cambodians to relocate to labour camps in the countryside, where mass executions, forced labour, physical abuse, malnutrition, and disease were rampant. They also started the “Maha Lout Ploh”, copying the “Great Leap Forward” of China that caused tens of millions of deaths in the Great Chinese Famine. In 1976, the Khmer Rouge changed the name of the country to Democratic Kampuchea.

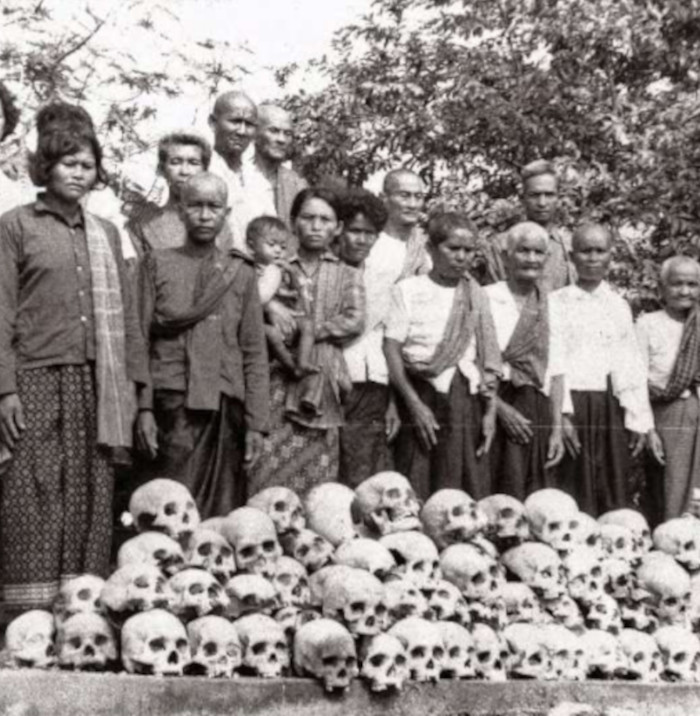

By January 1979, 1.5 to 2 million people had died due to the Khmer Rouge's policies, including 200,000-300,000 Chinese Cambodians, 90,000 Muslims, and 20,000 Vietnamese Cambodians. 20,000 people passed through the Security Prison 21, one of the 196 prisons the Khmer Rouge operated, and only seven adults survived. The prisoners were taken to the Killing Fields, where they were executed (often with pickaxes, to save bullets) and buried in mass graves.

Abduction and indoctrination of children was widespread, and many were persuaded or forced to commit atrocities. As of 2009, the Documentation Center of Cambodia has mapped 23,745 mass graves containing approximately 1.3 million suspected victims of execution. Direct execution is believed to account for up to 60% of the genocide's death toll, with other victims succumbing to starvation, exhaustion, or disease.

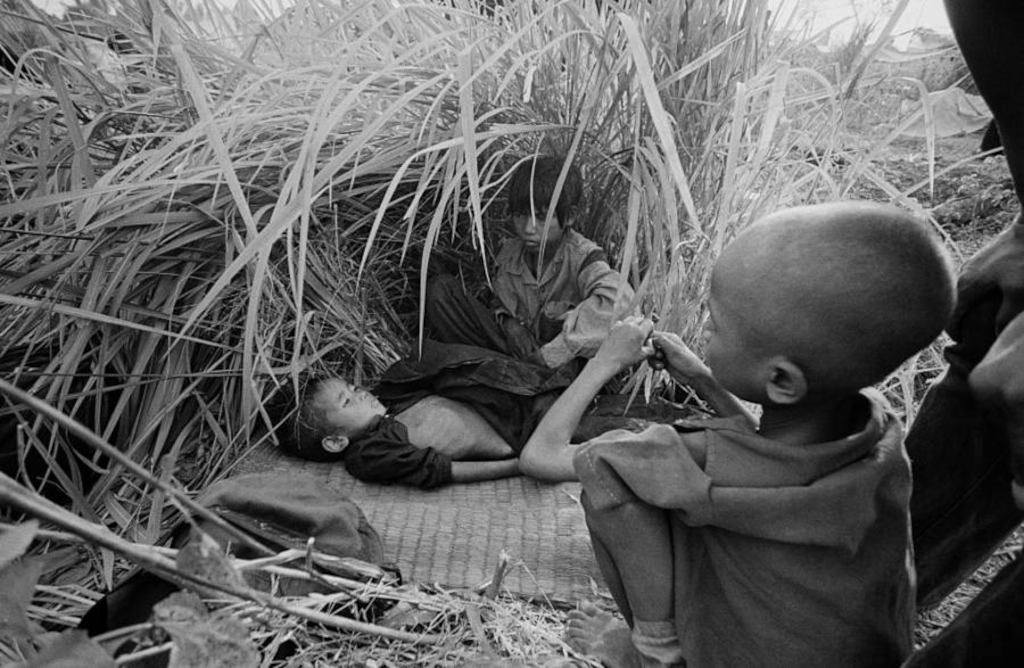

“Various studies have estimated the death toll at between 740,000 and 3,000,000, most commonly between 1.4 million and 2.2 million, with perhaps half of those deaths being due to executions, and the rest from starvation and disease. An additional 300,000 Cambodians starved to death between 1979 and 1980, largely as a result of the after-effects of Khmer Rouge policy.”.

The genocide triggered the second outflow of refugees, many of whom escaped to neighbouring Vietnam and, to a lesser extent, Thailand. The Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia ended the genocide by defeating the Khmer Rouge in January 1979. On 2 January 2001, the Cambodian government established the Khmer Rouge Tribunal to try the members of the Khmer Rouge leadership responsible for the Cambodian genocide. Trials began on 17 February 2009. On 7 August 2014, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan were convicted and received life sentences for crimes against humanity during the genocide.

“Anyone thought to be an intellectual of any sort was killed. Often people were condemned for wearing glasses or knowing a foreign language. Ethnic Vietnamese and Cham Muslims in Cambodia were also targeted. Hundreds of thousands of the educated middle-classes were tortured and executed in special centres.”.

In 1968, the Khmer Rouge officially launched a national insurgency across Cambodia. Though North Vietnam had not been informed of this decision, its forces provided shelter and weapons to the Khmer Rouge after the insurgency started. North Vietnamese support for the Khmer Rouge's insurgency made it impossible for the Cambodian military to effectively counter it. For the next two years, the insurgency grew because Norodom Sihanouk did very little to stop it. As the insurgency grew stronger, the party finally openly declared itself to be the Communist Party of Kampuchea.

Sihanouk was removed as head of state in 1970. Premier Lon Nol deposed him with the support of the National Assembly, establishing the pro-United States Khmer Republic. On the Communist Party of China (CPC)'s advice, Sihanouk, in exile in Beijing, made an alliance with the Khmer Rouge and became the nominal head of a Khmer Rouge–dominated government-in-exile (known by its French acronym, GRUNK) backed by China. Although thoroughly aware of the weakness of Lon Nol's forces and loath to commit American military force to the new conflict in any form other than airpower, the Nixon administration announced its support for the new Khmer Republic.

On 29 March 1970, North Vietnam launched an offensive against the Cambodian army. Documents uncovered from the Soviet Union's archives reveal that the invasion was launched at the Khmer Rouge's explicit request after negotiations were held with Nuon Chea. A North Vietnamese force quickly overran large parts of eastern Cambodia, reaching within 15 miles (24 km) of Phnom Penh before being pushed back. By June, three months after Sihanouk's removal, they had swept government forces from the entire northeastern third of the country. After defeating those forces, the North Vietnamese turned the newly won territories over to the local insurgents.

The Khmer Rouge also established “liberated” areas in the south and the southwestern parts of the country, where they operated independently of the North Vietnamese. After Sihanouk showed his support for the Khmer Rouge by visiting them in the field, their ranks swelled from 6,000 to 50,000 fighters. Many of the recruits were apolitical peasants who fought supporting the king, not for communism, of which they had little understanding. By 1975, with Lon Nol's government running out of ammunition and having lost U.S. support, it was clear that it was only a matter of time before it would collapse. On 17 April 1975, the Khmer Rouge captured Phnom Penh and ended the civil war.

Since the 1950s, Pol Pot had made frequent visits to the People's Republic of China, receiving political and military training—especially on the theory of Dictatorship of the proletariat—from the personnel of the CPC. From November 1965 to February 1966, high-ranking CPC officials such as Chen Boda and Zhang Chunqiao trained him on topics such as the communist revolution in China, class conflicts, Communist International, etc. Pol Pot also met with other officials, including Deng Xiaoping and Peng Zhen. He was particularly impressed by Kang Sheng's lecture on political purge.

In 1970, Lon Nol overthrew Sihanouk, and the latter fled to Beijing, where Pol Pot was also visiting. On the advice of CPC, Khmer Rouge changed its position to support Sihanouk, establishing the National United Front of Kampuchea. In 1970 alone, the Chinese reportedly gave the United Front 400 tons of military aid. In April 1974, Sihanouk and Khmer Rouge leaders Ieng Sary and Khieu Samphan met with Mao in Beijing; Mao agreed on the policies Khmer Rouge proposed but was against marginalising Sihanouk in a new Cambodia after winning the civil war. In 1975, Khmer Rouge defeated the Khmer Republic and started the Cambodian genocide.

In June 1975, Pol Pot and other Khmer Rouge officials met with Mao in Beijing, where Mao taught Pot his “Theory of Continuing Revolution under the Dictatorship of the Proletariat”, recommended two relevant articles by Yao Wenyuan, and sent him over 30 books authored by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin.

During the meeting, Mao said to Pol Pot:

“We agree with you! Much of your experience is better than ours. China is not qualified to criticise you. We committed errors of the political routes for ten times in fifty years—some are national, some are local…Thus, I say China has no qualification to criticise you but have to applaud you. You are basically correct…During the transition from the democratic revolution to adopting a socialist path, there exist two possibilities: one is socialism, the other is capitalism. Our situation now is like this. Fifty years from now, or one hundred years from now, the struggle between two lines will exist. Even ten thousand years from now, the struggle between two lines will still exist. When Communism is realised, the struggle between two lines will still be there. Otherwise, you are not a Marxist...... Our state now is, as Lenin said, a capitalist state without capitalists. This state protects capitalist rights, and the wages are not equal. Under the slogan of equality, a system of inequality has been introduced. There will exist a struggle between two lines, the struggle between the advanced and the backward, even when Communism is realised. Today, we cannot explain it completely”.

Pol Pot replied:

“The issue of lines of struggle raised by Chairman Mao is an important strategic issue. We will follow your words in the future. I have read and learned various works of Chairman Mao since I was young, especially the theory on people's war. Your works have guided our entire party”.

Year Zero

Year Zero is an idea put into practice by Pol Pot in Democratic Kampuchea that all culture and traditions within a society must be completely destroyed or discarded and that a new revolutionary culture must replace it starting from scratch. In this sense, all of the history of a nation or a people before Year Zero would be largely deemed irrelevant, because it would ideally be purged and replaced from the ground up. The first day of "Year Zero" was declared by the Khmer Rouge on 17 April 1975 upon their takeover of Cambodia in order to signify a rebirth of Cambodian history. Adopting the term as an analogy to the "Year One" of the French Revolutionary Calendar, Year Zero was effectually an attempt by the Khmer Rouge to erase history and reset Cambodian society to a zeroth year, removing any vestiges of the past.

In 1975, a Khmer Rouge spokesman declared, proudly that “2000 years” of Cambodian history had ended. I hope I’ve made it clear in these brief remarks not only that Cambodian history extends back further than 2000 years but also that it is fascinating to study, and one that Cambodians can be proud of.

Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, most of whom were French-educated communists, took inspiration from the concept of "Year One" in the French Revolutionary Calendar. The French "Year One" came about during the French Revolution when, after the abolition of the French monarchy on 20 September 1792, the National Convention instituted a new calendar and declared that date to be the beginning of Year I. Hoping to transform the nation into an agrarian utopia, communist leader Pol Pot set out to reconstruct the country into a pre-industrial, classless society by attempting to turn all citizens into rural agricultural workers rather than educated city dwellers, whom Pot and his regime believed to have been corrupted by western, capitalist ideas.

“The new rulers of Cambodia call 1975 "Year Zero", the dawn of an age in which there will be no families, no sentiment, no expressions of love or grief, no medicines, no hospitals, no schools, no books, no learning, no holidays, no music, no song, no post, no money – only work and death.”.

He declared that the nation would start again at "Year Zero", and everything that existed before Year Zero was to be eradicated. In other words, this was to be a complete and thorough reset (or even cleansing) of Cambodian society. He isolated his people from the global community; established rural collectives; dismantled the social fabric and infrastructure of Cambodia; and set about the emptying of cities, as well as the abolition of money (thus also destroying banks), private property, families, and religion. To build the new Cambodian society, the inhabitants of the depopulated cities were sent to labour camps. The people of Phnom Penh, in particular, were forced immediately to "return to the villages" to work. Similar evacuations occurred at Batdambang, Kampong Cham, Siem Reap, Kampong Thom, among others.

Knowledge of anything pre-Year Zero was prohibited. To ensure that there was no recorded memory of a pre-Year Zero society, books were burned. (Wearing glasses was also criminalised as it was taken to indicate that one might habitually read books.). In Democratic Kampuchea, the only acceptable lifestyle was that of peasant agricultural workers. Centuries of Cambodian culture and institutions were thereby eliminated—shutting down factories, hospitals, schools, and universities—along with anyone who expressed interest in their preservation. So-called New People—members of the old governments and intellectuals in general, including lawyers, doctors, teachers, engineers, clergy, and qualified professionals in all fields—were thought to be a threat to the new regime and were therefore especially singled out and executed during the purges accompanying Year Zero.

The Khmer Rouge's takeover was rapidly followed by a series of drastic revolutionary de-industrialisation policies which resulted in a death toll that vastly exceeded the toll that resulted from the French Reign of Terror.

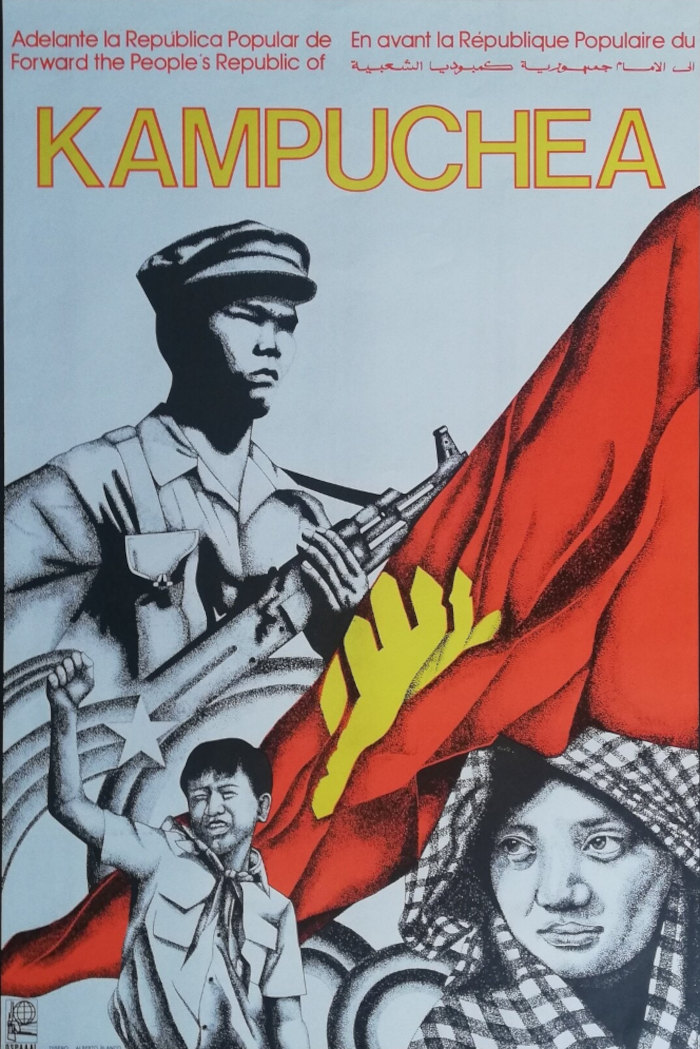

Democratic Kampuchea

Kampuchea , officially known as Democratic Kampuchea from 5 January 1976, was a one-party totalitarian state which encompassed modern-day Cambodia and existed from 1975 to 1979. It was controlled by the Khmer Rouge (KR), the name popularly given to the followers of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), and was founded when KR forces defeated the Khmer Republic of Lon Nol in 1975. The KR lost control of most Cambodian territory to the Vietnamese occupation. From 1979 to 1982, Democratic Kampuchea survived as a rump state. In June 1982, the Khmer Rouge formed the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) with two non-communist guerrilla factions, which retained international recognition. The state was renamed as Cambodia in 1990 in the run-up to the UN-sponsored 1991 Paris Peace Agreements.

“We are uniting, to construct a Kampuchea with a new and better society, democratic, egalitarian and just. We follow the road to firmly-based independence. We absolutely guarantee to defend our motherland, Our fine territory and our magnificent revolution!”.

In January 1976, the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) promulgated the Constitution of Democratic Kampuchea. The Constitution provided for a Kampuchean People's Representative Assembly (KPRA) to be elected by secret ballot in direct general elections and a State Praesidium to be selected and appointed every five years by the KPRA.

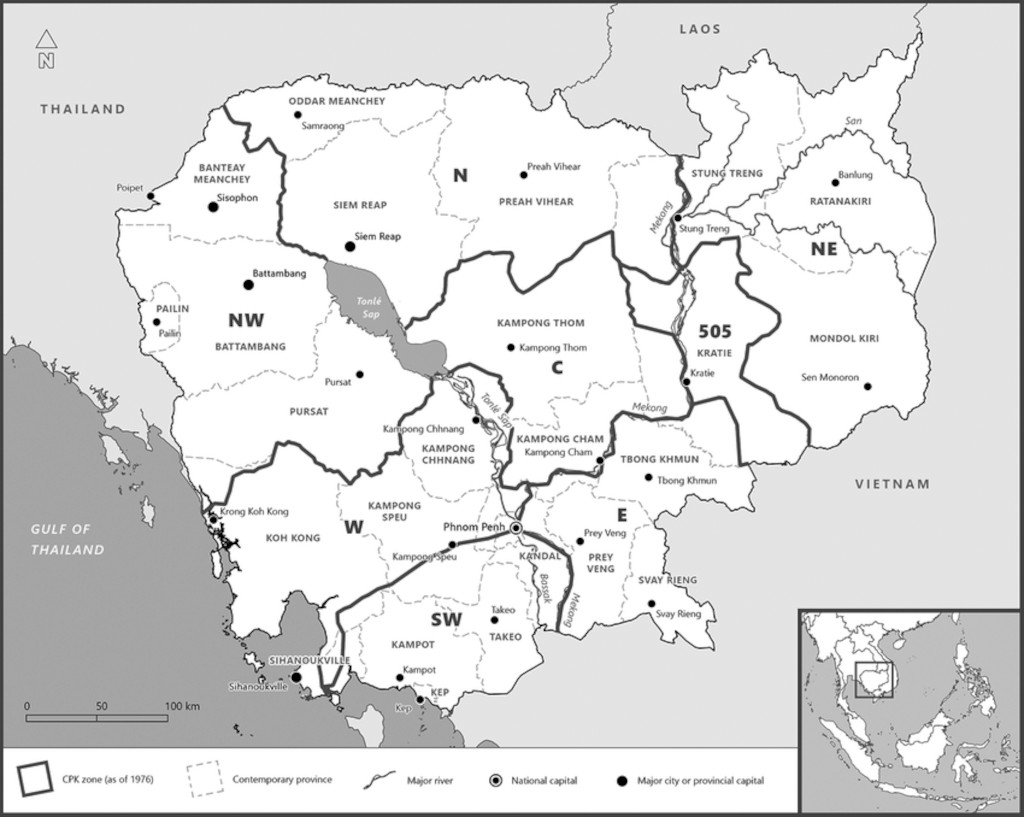

All power belonged to the Standing Committee of CPK, the membership of which comprised the Secretary and Prime Minister Pol Pot, his Deputy Secretary Nuon Chea and seven others. It was known also as the "Centre", the "Organisation" or "Angkar", and its daily work was conducted from Office 870 in Phnom Penh. For almost two years after the takeover, the Khmer Rouge continued to refer to itself as simply Angkar.

The Constitution defined Democratic Kampuchea's foreign policy principles in Article 21, the document's longest, in terms of "independence, peace, neutrality, and nonalignment." It pledged the country's support to anti-imperialist struggles in the Third World. The "rights and duties of the individual" were briefly defined in Article 12. They included none of what are commonly regarded as guarantees of political human rights except the statement that "men and women are equal in every respect." The document declared, however, that "all workers" and "all peasants" were "masters" of their factories and fields. An assertion that "there is absolutely no unemployment in Democratic Kampuchea" rings true in light of the regime's massive use of force.

The Khmer Rouge destroyed the legal and judicial structures of the Khmer Republic. There were no courts, judges, laws or trials in Democratic Kampuchea. The "people’s courts" stipulated in Article 9 of the Constitution were never established. The old legal structures were replaced by re-education, interrogation and security centres where former Khmer Republic officials and supporters as well as others were detained and executed. According to Pol Pot, Cambodia was made up of four classes: peasants, proletariat, bourgeoisie, and feudalists. Post-revolutionary society, as defined by the 1976 Constitution of Democratic Kampuchea, consisted of workers, peasants, and "all other Kampuchean working people." No allowance was made for a transitional stage such as China's New Democracy in which "patriotic" landlord or bourgeois elements were permitted to play a role in socialist construction.

Cambodian statesman Norodom Sihanouk writes that in 1975 he, Khieu Samphan, and Khieu Thirith went to visit Zhou Enlai, who was gravely ill. Zhou warned them not to attempt to achieve communism in a single step, as China had attempted in the late 1950s with the Great Leap Forward. Khieu Samphan and Khieu Thirith "just smiled an incredulous and superior smile." Khieu Samphan and Son Sen later boasted to Sihanouk that "we will be the first nation to create a completely communist society without wasting time on intermediate steps".

Although conditions varied from region to region, a situation that was, in part, a reflection of factional divisions that still existed within the CPK during the 1970s, the testimony of refugees reveals that the most salient social division was between the politically suspect "new people", those driven out of the towns after the communist victory, and the more reliable "old people", the peasants who had remained in the countryside. The number of "new people" may initially have been as high as 2.5 million.

The "new people" were treated as forced labourers. They were constantly moved, were forced to do the hardest physical labour, and worked in the most inhospitable, fever-ridden parts of the country, such as forests, upland areas, and swamps. "New people" were segregated from "old people", enjoyed little or no privacy, and received the smallest rice rations. When the country experienced food shortages in 1977, the "new people" suffered the most. New People were not allowed any property.

One of the Khmer Rouge mottos, in reference to the New People, was "To keep you is no benefit. To destroy you is no loss."

Families often were separated because people were divided into work brigades according to age and sex and sent to different parts of the country. "New people" were subjected to unending political indoctrination and could be executed without trial. The situation of the "old people" under Khmer Rouge rule was more ambiguous. Refugee interviews reveal cases in which villagers were treated as harshly as the "new people", enduring forced labour, indoctrination, the separation of children from parents, and executions; however, they were generally allowed to remain in their native villages. Because of their age-old resentment of the urban and rural elites, many of the poorest peasants probably were sympathetic to Khmer Rouge's goals.

Although the Southwestern Zone was one original centre of power of the Khmer Rouge, and cadres administered it with strict discipline, random executions were relatively rare, and "new people" were not persecuted if they had a cooperative attitude. In the Western Zone and in the Northwestern Zone, conditions were harsh. Starvation was general in the latter zone because cadres sent rice to Phnom Penh rather than distributing it to the local population. In the Northern Zone and in the Central Zone, there seem to have been more executions than there were victims of starvation.

On the surface, society in Democratic Kampuchea was strictly egalitarian. The Khmer language, like many in Southeast Asia, has a complex system of usages to define speakers' rank and social status. These usages were abandoned, neologisms were introduced, and everyday vocabulary was altered to encourage a more collectivist mentality. People were encouraged to call each other "friend", or "comrade" (in Khmer, មតដ mitt), and to avoid traditional signs of deference such as bowing or folding the hands in salutation. They were also encouraged to talk about themselves in the plural "we" rather than the singular "I". Aspects of life from the Khmer Republic such as art, television, mail, books, movies, music, and personal vehicles were prohibited.

The language was transformed in other ways. The Khmer Rouge invented new terms. People were told they must "forge" (lot dam) a new revolutionary character, that they were the "instruments" (opokar) of the Angkar, and that nostalgia for pre-revolutionary times (chheu satek arom, or "memory sickness") could result in their receiving Angkar's "invitation" to be deindustrialised and to live in a concentration camp. Despite the ideological commitment to radical equality, CPK members, local-level leaders of poor peasant backgrounds who collaborated with Angkar, and the armed forces constituted a clearly recognisable elite. They had a higher standard of living and received special privileges not enjoyed by the rest of the population. Refugees agree that, even during times of severe food shortages, members of the grassroots elite had adequate, if not luxurious, supplies of food.

One refugee wrote that "pretty new bamboo houses" were built for Khmer Rouge cadres along the river in Phnom Penh. Members of the Central Committee could go to China for medical treatment, and the highest echelons of the party had access to imported luxury products.

The Khmer Rouge regime was also characterised by "totalitarian puritanism" with any sex before marriage being punishable by death in many cooperatives and zones. The Khmer Rouge regarded traditional education with undiluted hostility. After the fall of Phnom Penh, they executed thousands of teachers. Those who had been educators prior to 1975 survived by hiding their identities. For a regime at war with most of Cambodia's traditional values, education meant that it was necessary to create a gap between the values of the young and the values of the nonrevolutionary old.

The regime recruited children to spy on adults. The pliancy of the younger generation made them, in Angkar's words, the "dictatorial instrument of the party.". In 1962 the communists had created a special secret organisation, the Democratic Youth League, that, in the early 1970s, changed its name to the Communist Youth League of Kampuchea. Pol Pot considered Youth League alumni as his most loyal and reliable supporters and used them to gain control of the central and the regional CPK apparatus. Hardened young cadres, many little more than twelve years of age, were enthusiastic accomplices in some of the regime's worst atrocities. Sihanouk, who was kept under virtual house arrest in Phnom Penh between 1976 and 1978, wrote in War and Hope that his youthful guards:

Having been separated from their families and given a thorough indoctrination, were encouraged to play cruel games involving the torture of animals.

Having lost parents, siblings, and friends in the war and lacking the Buddhist values of their elders, the Khmer Rouge youth also lacked the inhibitions that would have dampened their zeal for revolutionary terror. Article 20 of the 1976 Constitution of Democratic Kampuchea guaranteed religious freedom, but it also declared that "all reactionary religions that are detrimental to Democratic Kampuchea and the Kampuchean People are strictly forbidden." About 85 percent of the population followed the Theravada school of Buddhism. The country's 40,000 to 60,000 Buddhist monks, regarded by the regime as social parasites, were defrocked and forced to work in the rural co-operatives and irrigation projects.

Many monks were executed; temples and pagodas were destroyed or turned into storehouses. Images of the Buddha were defaced and dumped into rivers and lakes. People who were discovered praying or expressing religious sentiments were often killed. The Christian and Muslim communities also were even more persecuted, as they were labelled as part of a pro-Western cosmopolitan sphere, hindering Cambodian culture and society. The Roman Catholic cathedral of Phnom Penh was completely razed. The Khmer Rouge forced Muslims to eat pork, which they regard as forbidden (ḥarām). Many of those who refused were killed. Christian clergy and Muslim imams were executed. One hundred and thirty Cham mosques were destroyed.

The Khmer Rouge banned by decree the existence of ethnic Chinese, Vietnamese, Muslim Cham, and 20 other minorities, which altogether constituted 15% of the population at the beginning of the Khmer Rouge's rule. Tens of thousands of Vietnamese were raped, mutilated, and murdered in regime-organised massacres. Most of the survivors fled to Vietnam. The Cham, a Muslim minority who are the descendants of migrants from the old state of Champa, were forced to adopt the Khmer language and customs. Their communities, which traditionally had existed apart from Khmer villages, were broken up. Forty thousand Cham were killed in two districts of Kampong Cham Province alone. Thai minorities living near the Thai border also were persecuted.

At the beginning of the Khmer Rouge's rule in 1975, there were 425,000 ethnic Chinese in Cambodia. By the end in 1979, there were 200,000.

The state of the Chinese Cambodians was described as "the worst disaster ever to befall any ethnic Chinese community in Southeast Asia". Cambodians of Chinese descent were massacred by the Khmer Rouge under the justification that they "used to exploit the Cambodian people". Among the Khmer, the Chinese were also resented for their lighter skin color and cultural differences. Hundreds of Chinese families were rounded up in 1978 and told that they were to be resettled, but were actually executed. . In addition to being a proscribed ethnic group by the government, the Chinese were predominantly city-dwellers, making them vulnerable to the Khmer Rouge's revolutionary ruralism.

Genocide

During the genocide, China was the Khmer Rouge's main international patron, supplying “more than 15,000 military advisers” and most of its external aid. It is estimated that at least 90% of foreign aid to Khmer Rouge came from China, with 1975 alone seeing US$1 billion in interest-free economics and military aid, “the biggest aid ever given to anyone country by China”. But a series of internal crises in 1976 prevented Beijing from exerting substantial influence over Khmer Rouge policies. Ideology played an important role in the genocide. Pol Pot was influenced by Marxism and wanted an entirely self-sufficient agrarian society free of foreign influence.

Mass murderer Joseph Stalin's work has been described as a “crucial formative influence” on his thought. Also, heavily influential was Mao's work, particularly On New Democracy. In the mid-1960s, Pol Pot reformulated his ideas about Marxism-Leninism to suit the Cambodian situation, aiming to bring Cambodia back to its “mythic past” of the powerful Khmer Empire, to stop corrupting influences like foreign aid and western culture, and to restore an agrarian society.

Pol Pot's strong belief in an agrarian utopia stemmed from his experience in Cambodia's rural northeast, where, while the Khmer Rouge gained power, he developed an affinity for the agrarian self-sufficiency of the area's isolated tribes. Attempts to implement these goals (formed from small rural communes) into a larger society were key factors in the ensuing genocide. One Khmer Rouge leader said the killings were meant for the “purification of the populace.”

“One estimate is that out of 40,000 to 60,000 monks, only between 800 and 1,000 survived to carry on their religion. We do know that of 2,680 monks in eight monasteries, a mere seventy were alive as of 1979. As for the Buddhist temples that populated the landscape of Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge destroyed 95 percent of them, and turned the remaining few into warehouses or allocated them for some other degrading use. Amazingly, in the very short span of a year or so, the small gang of Khmer Rouge wiped out the centre of Cambodian culture, its spiritual incarnation, its institutions….As part of a planned genocide campaign, the Khmer Rouge sought and killed other minorities, such as the Moslem Cham. In the district of Kompong Xiem, for example, they demolished five Cham hamlets and reportedly massacred 20,000 that lived there; in the district of Koong Neas only four Cham apparently survived out of some 20,000”.

The Khmer Rouge forced virtually Cambodia's entire population into mobile work teams. Michael Hunt has written that it was “an experiment in social mobilisation unmatched in twentieth-century revolutions.” The Khmer Rouge used an inhumane forced labour regime, starvation, forced resettlement, land collectivisation, and state terror to keep the population in line. Ben Kiernan has compared the Cambodian genocide to the Armenian Genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire during The First World War.

“the purest genocide of the Cold War era”.

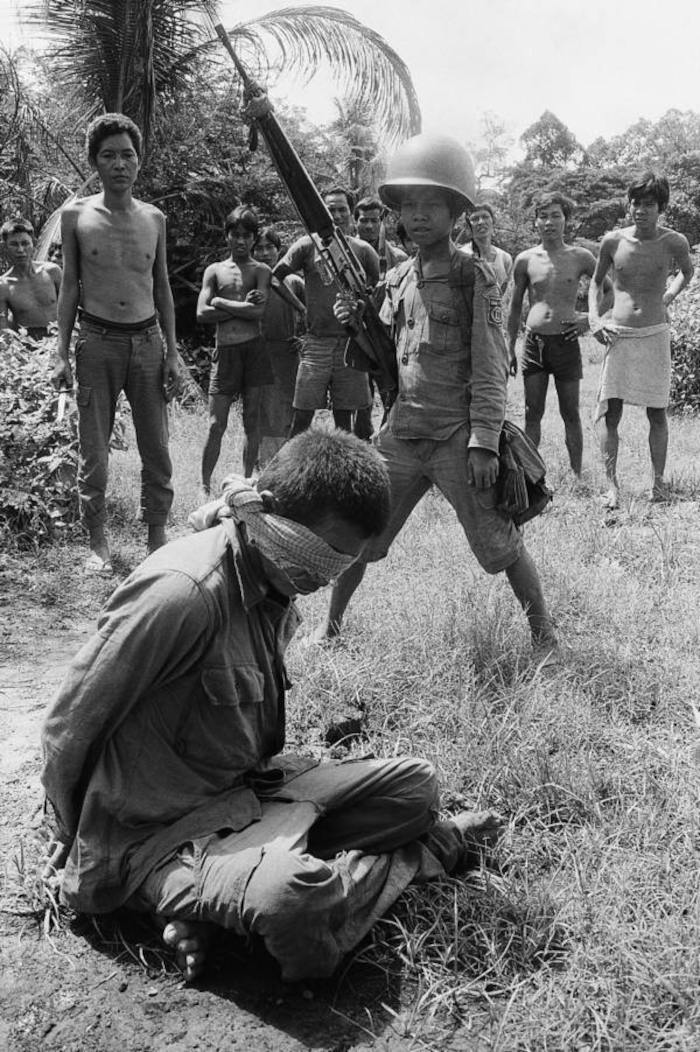

The Khmer Rouge regime frequently arrested and often executed anyone suspected of connections with the former Cambodian government or foreign governments, as well as professionals, intellectuals, the Buddhist monkhood, and ethnic minorities. Even those who were stereotypically thought of as having intellectual qualities, such as wearing glasses or speaking multiple languages, were executed for fear that they would rebel against the Khmer Rouge. As a result, Pol Pot has been described by journalists and historians such as William Branigin as “a genocidal tyrant”.

Ben Kiernan estimates that about 1.7 million people were killed. Researcher Craig Etcheson of the Documentation Center of Cambodia suggests that the death toll was between 2 and 2.5 million, with a "most likely" figure of 2.2 million. After five years of researching some 20,000 grave sites, he concludes that "these mass graves contain the remains of 1,386,734 victims of execution". A United Nations investigation reported 2–3 million dead, while UNICEF estimated 3 million had been killed. Demographic analysis by Patrick Heuveline suggests that between 1.17 and 3.42 million Cambodians were killed, while Marek Sliwinski suggests that 1.8 million is a conservative figure.

Even the Khmer Rouge acknowledged that 2 million had been killed—though they attributed those deaths to a subsequent Vietnamese invasion. By late 1979, UN and Red Cross officials were warning that another 2.25 million Cambodians faced death by starvation due to "the near destruction of Cambodian society under the regime of ousted Prime Minister Pol Pot", who were saved by international aid after the Vietnamese invasion. British sociologist Martin Shaw described the Cambodian genocide as “the purest genocide of the Cold War-era”.

The attempt to purify Cambodian society along racial, social and political lines led to purges of Cambodia's previous military and political leadership, along with business leaders, journalists, students, doctors, and lawyers. Ethnic Vietnamese, ethnic Thai, ethnic Chinese, ethnic Cham, Cambodian Christians, and other minorities were also targeted. The Khmer Rouge forcibly relocated minority groups and banned their languages. By decree, the Khmer Rouge banned the existence of more than 20 minority groups, which constituted 15% of the country's population.

The judicial process of the Khmer Rouge regime, for minor or political crimes, began with a warning from the Angkar, the government of Cambodia under the regime. People receiving more than two warnings were sent for "re-education," which meant near-certain death. People were often encouraged to confess to Angkar their "pre-revolutionary lifestyles and crimes" (which usually included some kind of free-market activity; having had contact with a foreign source, such as a U.S. missionary, international relief or government agency; or contact with any foreigner or with the outside world at all), being told that Angkar would forgive them and "wipe the slate clean." They were then taken away to a place such as Tuol Sleng or Choeung Ek for torture and/or execution.

The executed were buried in mass graves. In order to save ammunition, the executions were often carried out using poison or improvised weapons such as sharpened bamboo sticks, hammers, machetes and axes. Inside the Buddhist Memorial Stupa at Choeung Ek, there is evidence of bayonets, knives, wooden clubs, hoes for farming and curved scythes being used to kill victims, with images of skulls, damaged by these implements, as evidence. In some and extreme cases the children and infants of adult victims were killed by having their heads bashed against the trunks of Chankiri trees, and then were thrown into the pits alongside their parents. The rationale was:

“to stop them growing up and taking revenge for their parents' deaths.”.

Some victims were required to dig their own graves; their weakness often meant that they were unable to dig very deep. The soldiers who carried out the executions were mostly young men or women from peasant families.

Killing Fields

The Killing Fields are a number of sites in Cambodia where collectively more than 1,000,000 people were killed and buried by the Khmer Rouge regime (the Communist Party of Kampuchea) during its rule of the country from 1975 to 1979, immediately after the end of the Cambodian Civil War (1970–1975). The mass killings were part of a broad state-sponsored genocide (the Cambodian genocide).

Analysis of 20,000 mass grave sites by the DC-Cam Mapping Program and Yale University indicates at least 1,386,734 victims of execution. Estimates of the total deaths resulting from Khmer Rouge policies, including death from disease and starvation, range from 1.7 to 2.5 million out of a 1975 population of roughly 8 million. In 1979, Vietnam invaded Democratic Kampuchea and toppled the Khmer Rouge regime, ending the genocide.

The Khmer Rouge regime arrested and eventually executed almost everyone suspected of connections with the former government or with foreign governments, as well as professionals and intellectuals. As a result, Pol Pot has been described as "a genocidal tyrant".

Security Prison 21, Tuol Sleng

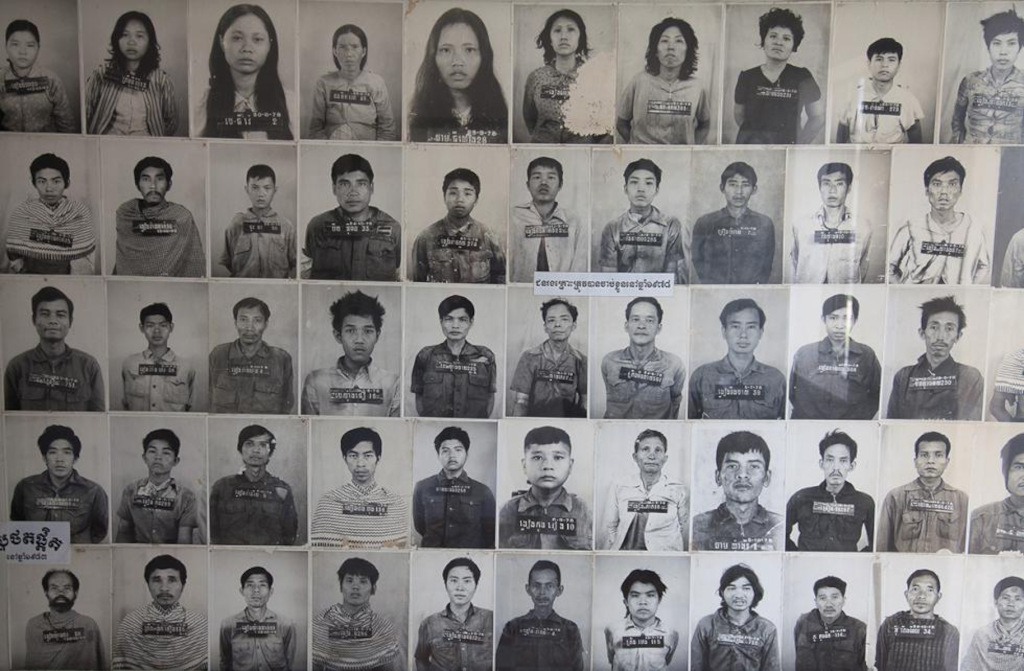

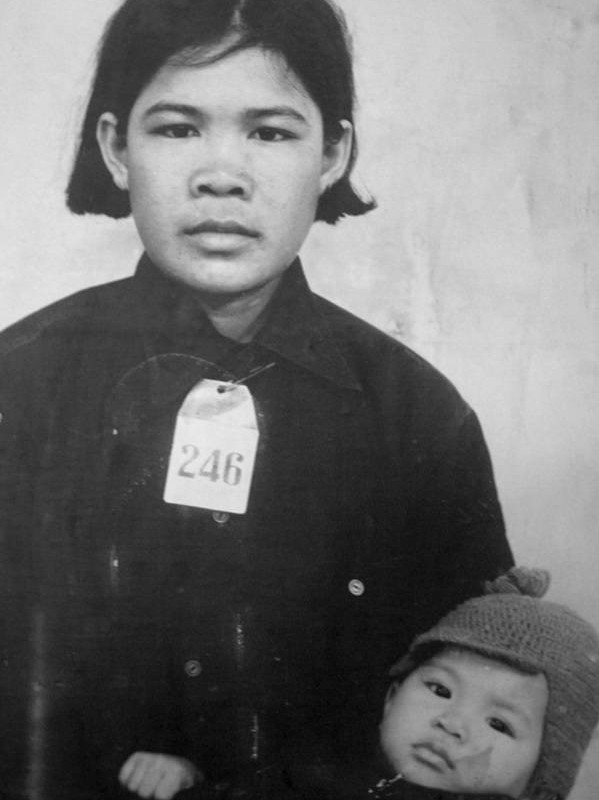

A security apparatus called Santebal was part of the Khmer Rouge organisational structure well before 17 April 1975, when the Khmer Rouge took control over Cambodia. The organisation was was overseen by Cambodian Communist politician and soldier Son Sen (alias "Comrade Khieu" or "Brother Number 89") and run by Kang Kek Iew (alias "Comrade Duch" or "Hang Pin"). The headquarters, originally located in small chapel in the capital, was a former high school known as Tuol Sleng, which could hold up to 1,500 prisoners. At the security center, code named S-21 (“S” for Santebal, the Khmer word meaning “state security organisation” and “21” for the walky-talky number of former prison chief Nath), prisoners were brought in, often handcuffed, to be photographed, interrogated, tortured, and executed.

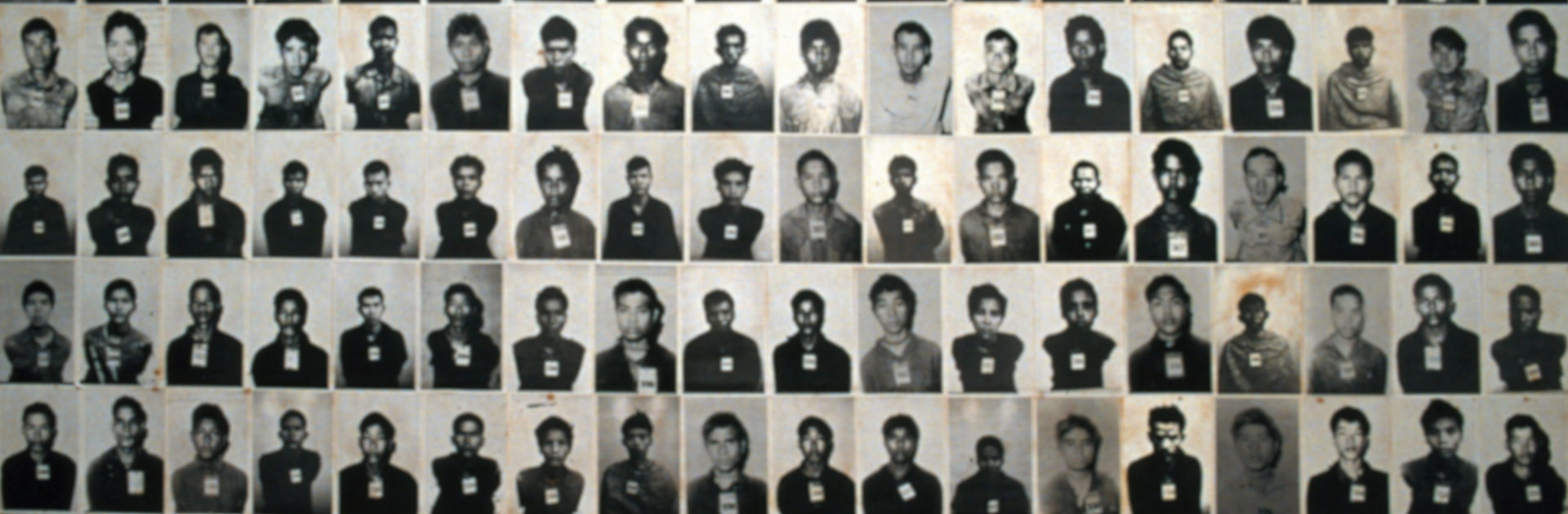

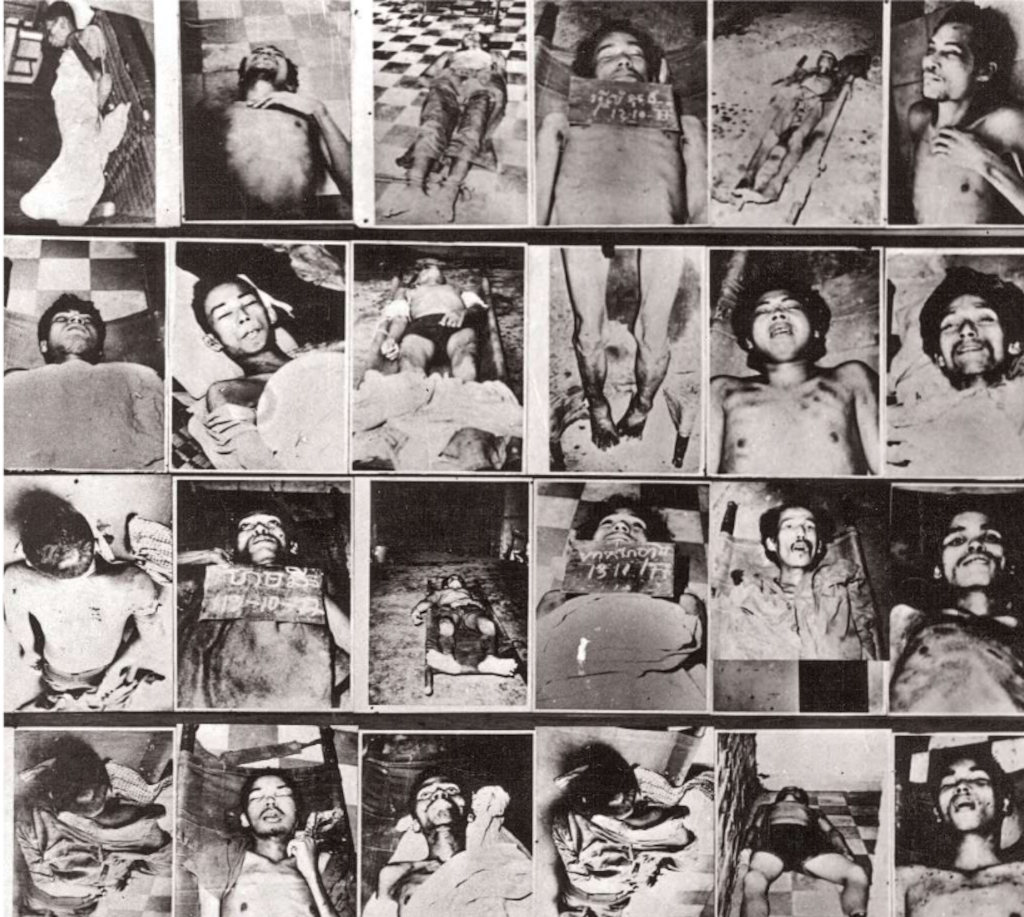

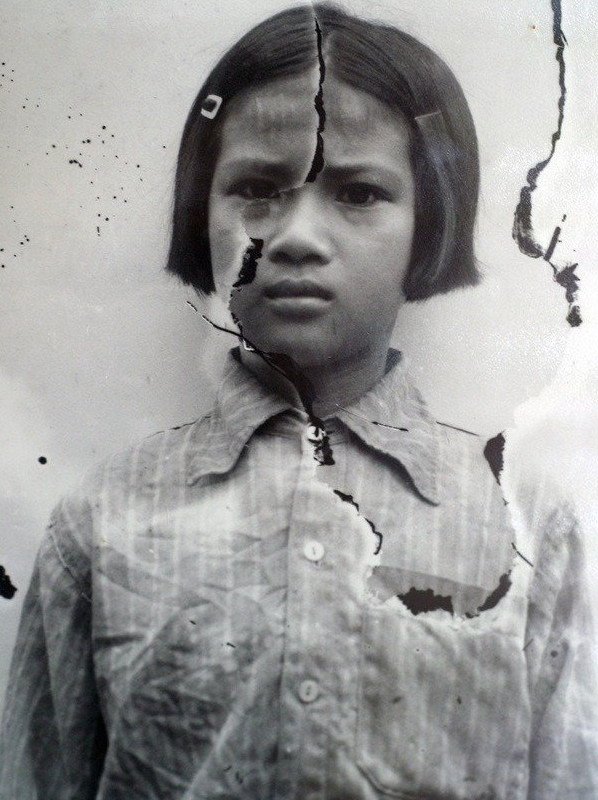

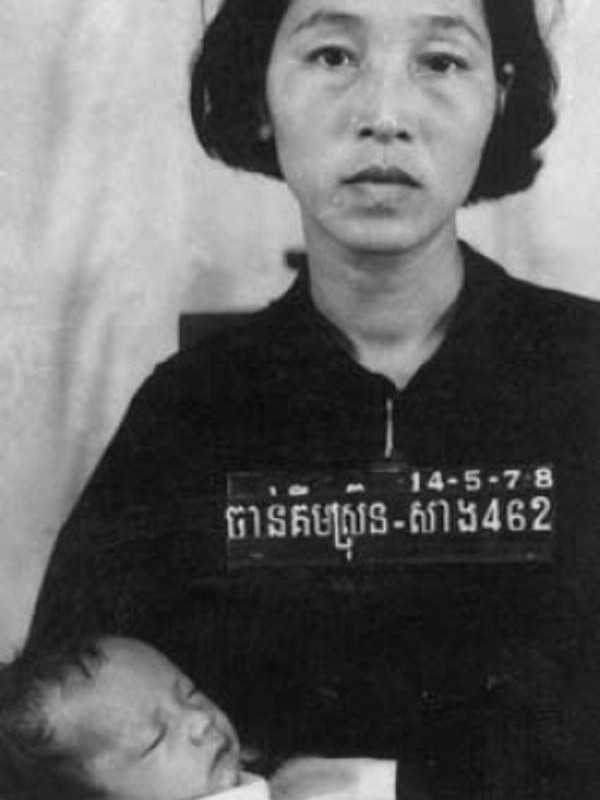

From 1975 to 1979, an estimated 20,000 people accused of crimes against the state or of espionage [accused of collaborating with foreign governments, spying for the CIA and the KBG] including high level officials such as ministers, and their family members were taken to Tuol Sleng. Offenses that could lead to such a fate could be as minor as breaking a factory machine or mishandling farming tools. Prisoners were also believed to be have conspired with others and thus were forced to reveal their “strings of traitors,” which sometimes included over one hundred names.

The Khmer Rouge government arrested, tortured, and eventually executed anyone suspected of belonging to several categories of supposed "enemies":

- Anyone with connections to the former government or with foreign governments.

- Professionals and intellectuals—in practice this included almost everyone with an education, people who understood a foreign language, and even people who required glasses. However, ironically, Pol Pot himself was a university-educated man (albeit a drop-out) with a taste for French literature and was also a fluent French speaker. Many artists, including musicians, writers, and filmmakers were executed. Some like Ros Serey Sothea, Pen Ran, and Sinn Sisamouth gained posthumous fame for their talents and are still popular with Khmers today.

- Ethnic Vietnamese, ethnic Chinese, ethnic Thai and other minorities in Eastern Highland, Cambodian Christians (most of whom were Catholic, and the Catholic Church in general), Muslims and the Buddhist monks.

- "Economic saboteurs:" many of the former urban dwellers (who had not starved to death in the first place) were deemed to be guilty by virtue of their lack of agricultural ability.

Often times, the entire family of a prisoner were captured and taken to Tuol Sleng, where their fate was shared with their accused relative. The interrogators at S-21 based their technique on a list of 10 security regulations which included, “While getting lashes or electrification you must not cry at all.”

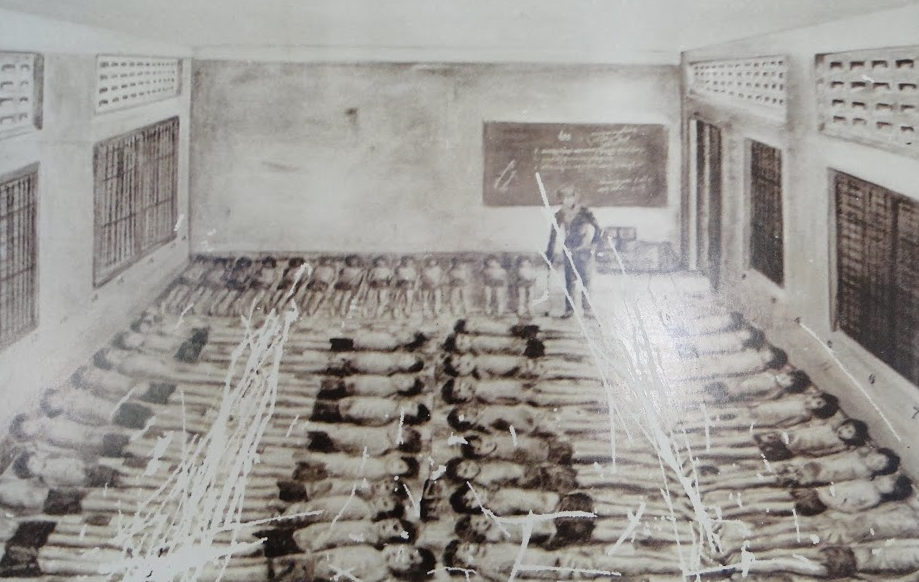

Upon arrival, prisoners were asked to provide a detailed biography of their life up to their detainment, and were then photographed before being placed in the prison.Tuol Sleng held up to 1,500 prisoners at a time. All lived in unhygienic and inhumane conditions. Prisoners were forbidden to speak to one another and spent their days shackled to either the wall or each other.

Prisoners were given two bowls of rice porridge and one bowl of leaf soup a day. Once every four days, prisoners were hosed down en masse by prison staff.

Interrogations began within a few days of incarceration in the “cold” unit, which could not use torture and instead relied on verbal coercion and “political pressure” to elicit confessions. If the confession taken by the cold unit was not sufficient, prisoners were then taken to the “hot unit,” which employed torture to get confessions.

Their methods included:

“beating with fists, feet, sticks or electric wire; burning with cigarettes; electric shocks; being forced to eat faeces; jabbing with needles; ripping out fingernails; suffocation with plastic bags; water boarding; and being covered with centipedes and scorpions.”.

Regulations for guards at S21:

- On duty, do not sit down or lean against the wall and do not write anything. Walk backward and forward.

- While guarding, absolutely do not ask the enemy’s names in the rooms or in the houses.

- While guarding, the concerned comrades must not leave the guard posts. Those who are not on duty absolutely do not get into and open the door or windows or question prisoners.

- Whether or not one knows, do not ask prisoners in the cells.

- You are not allowed to threaten or beat the prisoners. If the prisoners are undisciplined, you must immediately report by mouth or by letter to the concerned guards.

- If the prisoners take action to destroy keys, to cut their hands, to cut their necks or to swallow screws, you must take measures to handcuff them to their back and immediately report to the responsible guard

- When prisoners run away, you must immediately take steps to arrest them.

- While guarding, cadres in 50-soldier units have to be present at their respective guard posts as assigned by the party.

- While guarding, the cadres must not take naps or sit down; they have to constantly walk and control.

- While guarding, cadres and soldiers must absolutely check as directed. They have to check four times within twenty-four hours: 6 a.m., 11 a.m., 6 p.m. and 11 p.m.

- After checking, guards have to wait until all prisoners have dressed properly before leaving the rooms.

- You have to make sure all prisoners put on their clothing; do not allow them to take off their clothes.

- While guarding, responsible guards have to keep the keys on their own; do not be carefree or lazy. Absolutely do not lose the keys. If you lose them, do not destroy the lock; you have to find them and report it. If prisoners run away, you have to take responsibility in front of the collective.

- While guarding, you have to wear soldier uniforms. You are not allowed to wear short trousers or take off your shirt.

The confession process could last for weeks or months, and since full confessions were required, the medical unit was primarily tasked with keeping prisoners alive during interrogations. The product of these interrogations revealed more about the paranoid state of the Khmer Rouge than the prisoners: Confessions became intricate stories of coordinated attacks against the state with hundreds.

Confessions concluded with lists of co-conspirators that sometimes ran over a hundred people long. These supposed co-conspirators would then be interrogated and sometimes themselves brought to Security Prison 21. After confessions concluded, prisoners were handcuffed and forced to dig shallow pits that would be used as their own mass graves. Due to international sanctions and a collapsed economy, bullets became scarce in Cambodia. Instead of guns, executioners were forced to use makeshift weapons like pickaxes and iron bars to carry out mass executions. Oftentimes, their screams were covered with loudspeakers playing propaganda music of Democratic Kampuchea and noise from generator sets.

“Tortures were so atrocious and heinous that the prisoners tried in every way to commit suicide, even using spoons, and their hands were constantly tied behind their back to prevent them from committing suicide or trying to escape”.

Initially, prisoners were executed and buried near the premises of Security Prison 21, but by 1976, all available burial space around the prison had been used. After 1976, all prisoners were sent to the Choeung Ek execution centre, one of 150 used by the Khmer Rouge during the Cambodian genocide.

While the prisoners in the first years of the prison's operations were primarily members of the previous government, Khmer Rouge members suspected of being a threat to leadership were increasingly detained at Security Prison 21 during its later years. There, they would be interrogated by the “chew unit,” a unit formed solely for interrogating special cases.

Inside S-21, a special treatment was given to babies and children; they were taken away from their mothers and relatives, and sent to the Killing Fields, where they were smashed against the so-called Chankiri Tree. It was so the children “wouldn't grow up and take revenge for their parents' deaths”. Some of the soldiers laughed as they beat the children against the trees, as not laughing could have indicated sympathy, making oneself a target. A similar treatment is supposed to have been given to babies of other prisons like S-21, spread all over Democratic Kampuchea.

Similarly, prison staff had to obey nearly impossible regulations with fatal consequences if they failed to comply. From prison records, 563 guards and other staff of Tuol Sleng were executed. Non-Cambodians were also taken to Tuol Sleng, with 11 Westerners' cases being processed and then executed in the prison. Between 1976 and 1978, 20,000 Cambodians were imprisoned at Tuol Sleng. Of this number only seven adults are known to have survived. However, Tuol Sleng was only one of at least 150 execution centres in the country.

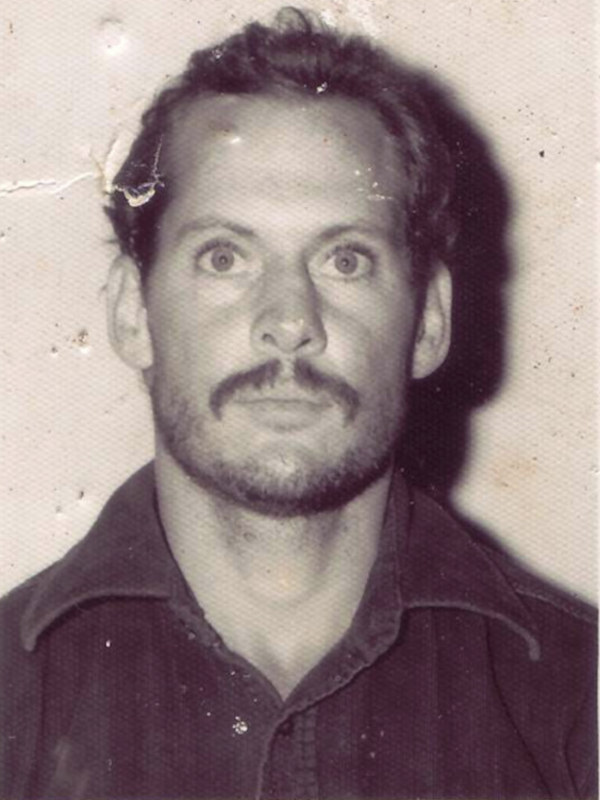

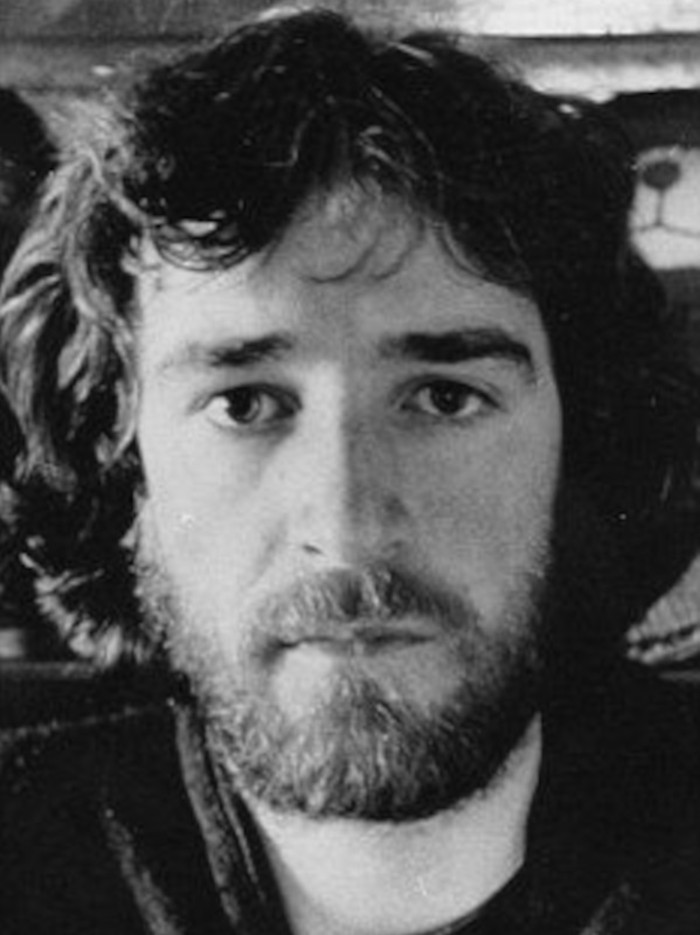

In the above photo is Christopher Edward DeLance, an American who mistakenly went into Cambodian waters in 1978. DeLance was forced to sign a confession that he was a CIA spy, and was subsequently executed a week before the Vietnamese invasion.

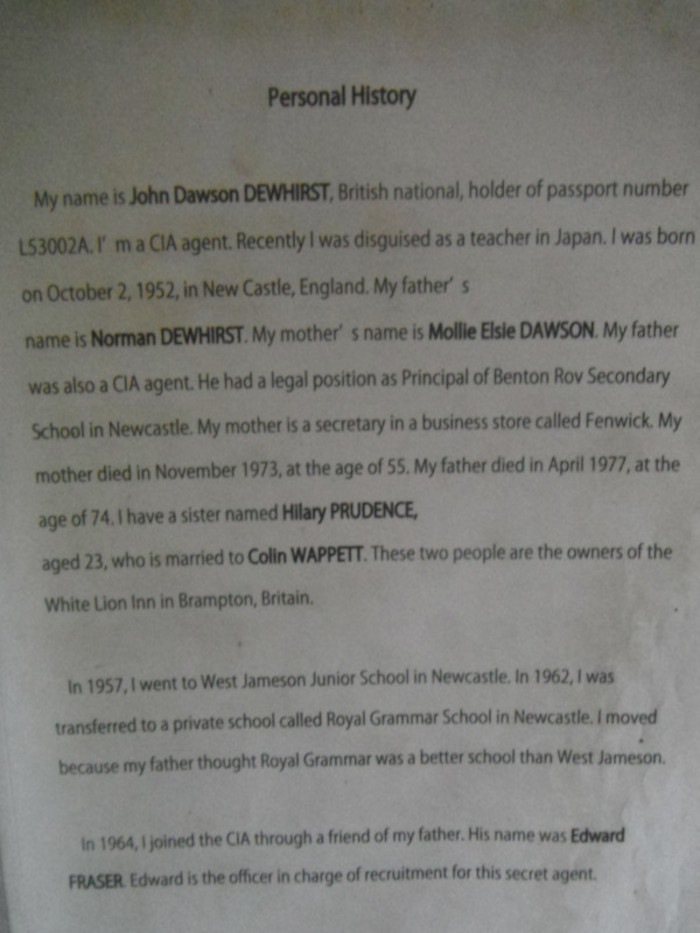

Alleged photographs and forced confessions of nine missing Western yachtsmen (four Americans, two Australians, plus those of John Dewhirst and Kerry Hamill) were found in the prison files. The confessions of Dewhirst and Hamill revealed that they had been seized by a Khmer Rouge patrol vessel near the island of Koh Tang on the evening of 13 August 1978. Stuart Glass, the Canadian befriended by Dewhirst and Hamill, had been shot and killed during Foxy Lady's capture. Hamill and Dewhirst were both brought ashore and then taken by truck to Phnom Penh.

Like the other Western yachtsmen, they were almost certainly tortured. The extent of their mistreatment is not clear. Dewhirst wrote several long confessions that mixed true events in his life with false accounts of his career as a CIA agent planning to subvert the Khmer Rouge regime. He claimed that his father (also an agent) had been paid a large bribe for inducting his son into the CIA, and that his college course in Loughborough was interspersed with training as a spy. Dewhirst and Hamill signed a series of confessions between 3 September and 13 October 1978.

During the 2009 trial of S-21 chief Kang Kek Iew, a former S-21 guard named Cheam Sour claimed that one of the eight Western yachtsmen held at S-21 was burned to death. Kang Kek Iew said that he received orders from his superiors that the bodies of the murdered westerners had to be burned to remove all traces of their remains, adding, “I believe that nobody would dare to violate my orders”.

After several years of research, however, the Documentation Center of Cambodia estimates that at least 179 prisoners were released from 1975-1978 and approximately 23 victims survived after Vietnam ousted the Khmer Rouge regime on January 7, 1979. The release status of the 179 prisoners (of which 100 were soldiers) is based on numerous Khmer Rouge documents and interviews compiled primarily by Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum senior archivist Mr. Nean Yin. Most of the 179 who were released disappeared or have died.

Party of Democratic Kampuchea

The Party of Democratic Kampuchea was a political party in Cambodia, formed as a continuation of the Communist Party of Kampuchea in December 1981. In the mid-1980s, it publicly claimed that its ideology was "a new form of democratic socialism", having ostensibly renounced Marxism–Leninism. According to the party itself, the dissolution of the CPK and formation of the PDK was prompted by the need for broader unity against Vietnam, a unity which an explicit communist line would hamper. The National Army of Democratic Kampuchea was the armed wing of the party, while the Patriotic and Democratic Front of the Great National Union of Kampuchea was a mass organisation controlled by it.

The General Secretary of the party at the time was Pol Pot. The party led the deposed Democratic Kampuchea government. Its followers were generally called Khmer Rouge. At the time of the formation of the PDK, the Khmer Rouge forces had been pushed back by the Vietnamese-backed KPRP government to an area near the Thai border. The PDK began cooperating with other anti-Vietnamese factions, and formed the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea in 1982. Although Pol Pot relinquished party leadership to Khieu Samphan in 1985, he continued to wield considerable influence over the movement.

Ahead of the 1992/1993 elections, the PDK was largely succeeded by the Cambodian National Unity Party (CNUP), which publicly stated its wish to participate in the elections but eventually did not register and vowed to sabotage the election. Subsequently, UNTAC decided not to conduct elections in areas under PDK control. At the time it was estimated that approximately six percent of the population in Cambodia lived in areas under PDK control. The PDK was declared illegal in July 1994, after which its activities continued under the Cambodian National Unity Party and the self-proclaimed Provisional Government of National Union and National Salvation of Cambodia.

National Army of Democratic Kampuchea

NADK was formed in December 1979 in order to replace the Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea. NADK forces consisted mainly of former RAK troops – large numbers of whom had escaped the 1978 to 1979 Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia. The New York Times reported in June 1987 that "the Khmer Rouge army is believed to be having some success in its recruitment, not only among the refugees in its camps but within the Vietnamese controlled People's Republic of Kampuchea." The NADK did not make personnel figures public, but estimates by military observers and by journalists generally ranged between 40,000 and 50,000 combatants in the 1980s.

In 1987 the opinion that the NADK was "the only effective fighting force" opposing the Vietnamese was more often expressed by Western observers. In an interview published in the United States in May 1987, prince Norodom Sihanouk reportedly said:

“Without the Khmer Rouge, we have no credibility on the battlefield... [they are]... the only credible military force.”.

During the 1980s, the Khmer Rouge leadership, composed of party cadres who doubled as military commanders, remained fairly constant. Pol Pot retained an ambiguous but presumably prominent position in the hierarchy, although he was nominally replaced as commander in chief of the NADK by Son Sen, who like Pol Pot had also been a student in Paris and who had gone underground with him in 1963.

There were reports of factions in the NADK, such as one loyal to Khieu Samphan, prime minister of the defunct regime of Democratic Kampuchea, and his deputy Ieng Sary, and another identified with Pol Pot and Ta Mok (the Southwestern Zone commander who conducted extensive purges of party ranks in Cambodia in 1977 to 1978). Although led by party and military veterans, the NADK combatants in 1987 were reportedly "less experienced, less motivated, and younger" than those the Vietnamese had faced in previous encounters. Nevertheless, the new Khmer Rouge recruits still were "hardy and lower class," and tougher than the non-communist combatants.

National Army of Democratic Kampuchea was title of a dual language glossy colour A4 photo magazine produced to advertise the activities of the NADK throughout the 1980s. It was a bimonthly publication that consisted of a steady diet of photographs showing NADK combatants going to the front, talking to villagers, with capture enemy supplies, defecting Khmer soldiers and on patrol, engaged in sabotage or preparing ambushes throughout the battlefields of Cambodia.

The photos served to illustrate the extent of the area of operations of NADK forces within occupied Cambodia, and reinforce its reputation as a credible military force. There were occasional maps, battlefield reports and up-dates on military activities that accompanied the Khmer language political reportage on the Coalition Government.

In carrying on its protracted insurgency, the NADK received the bulk of its military equipment and financing from China, which had supported the previous regime of Democratic Kampuchea. One pro-Beijing source put the level of Chinese aid to the NADK at US$1 million a month. Another source, although it did not give a breakdown, set the total level of Chinese assistance, to all the resistance factions, at somewhere between US$60 million and US$100 million a year. The Chinese weaponry observed in the possession of NADK combatants included Type 56 assault rifles, RPD light machine guns, Type 69 RPG launchers, recoilless rifles, and anti-personnel mines. NADK guerrillas usually were seen garbed in dark green Chinese fatigues and soft "Mao caps" without insignia. No markings or patches were evident on guerrilla uniforms, although the NADK had promulgated a hierarchy of ranks with distinctive insignias in 1981.

NADK continued fighting Cambodian government forces into the late 1990s. After the factional struggles when Pol Pot died in 1998, the last fighters were on the defensive from government soldiers and the estimated NADK troop strength stood at 2,000 fighters. The Party of Democratic Kampuchea (PDK) formed in December 1979, was declared illegal in 1994.

Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea

After the Khmer Rouge regime was overthrown, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping was unhappy with Vietnam's influence over the PRK government. Deng proposed to Sihanouk that he co-operate with the Khmer Rouge to overthrow the PRK government, but Sihanouk rejected it, as he opposed the genocidal policies pursued by the Khmer Rouge while they were in power. In March 1981, Sihanouk established a resistance movement, FUNCINPEC, which was complemented by a small resistance army known as Armée Nationale Sihanoukiste. He appointed In Tam, who had briefly served as prime minister in the Khmer Republic, as the commander-in-chief of ANS.

The ANS needed military aid from China, and Deng seized the opportunity to sway Sihanouk into collaborating with the Khmer Rouge. Sihanouk reluctantly agreed, and started talks in March 1981 with the Khmer Rouge and the Son Sann-led KPNLF on a unified anti-PRK resistance movement. After several rounds of negotiations mediated by Deng and Singapore's prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, FUNCINPEC, KPNLF, and the Khmer Rouge agreed to form the CGDK in June 1982. The CGDK was headed by Sihanouk, and functioned as a government-in-exile.

“Although the PDK was for the most part isolated from diplomacy, their National Army of Democratic Kampuchea were the largest and most effective armed forces of the CGDK.”.

Prior to the formation of the CGDK political coalition, in the late 1980s and early 1990s the Sonn Sann and Sihanouk opposition forces, then known as the KPNLF and FUNCINPEC, drew some military and financial support from the United States, which sought to assist these two movements as part of the Reagan Doctrine effort to counter Soviet and Vietnamese involvement in Cambodia. In 1984 and 1985, the Vietnamese army's offensives severely weakened the CGDK troops' positions, in effect eliminating the two non-communist factions as military players, leaving the Khmer Rouge as the sole military force of importance of the CGDK.

In 1990, in the run up to the United Nations sponsored Paris Peace Agreement of 1991 the CGDK renamed itself the National Government of Cambodia. It was dissolved in 1993, a year which saw the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia turn power over to the restored Kingdom of Cambodia. In July 1994, the Khmer Rouge would form an internationally unrecognised rival government known as the Provisional Government of National Union and National Salvation of Cambodia (in opposition to the established Kingdom of Cambodia).

Justice / Punishment

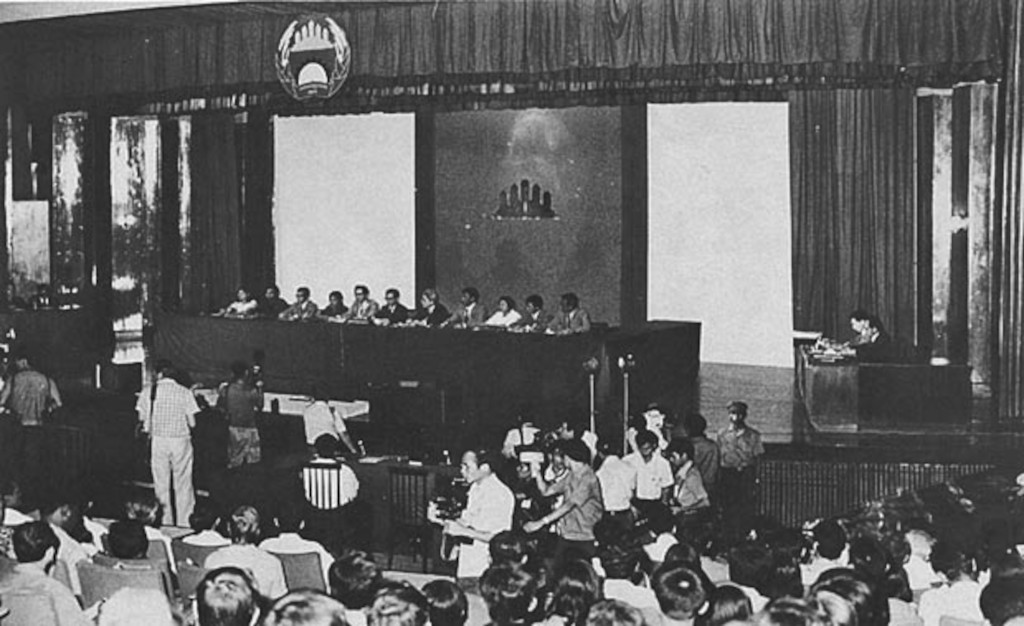

The People's Revolutionary Tribunal was a tribunal established by the People's Republic of Kampuchea in 1979 to try the Khmer Rouge leaders Pol Pot and Ieng Sary in absentia for genocide. The tribunal began seven months after the overthrow of Khmer Rouge's Democratic Kampuchea and was staffed by both Cambodian and international lawyers. The tribunal was held at Phnom Penh's Chaktomuk Theatre and transcripts of the proceedings were made available in Khmer, French and English. The court heard testimony from 39 witnesses over five days. The verdict, handed down on August 19, 1979, found the two leaders of the Khmer Rouge guilty of genocide, sentenced them to death and ordered the confiscation of their property.

Ieng Sary was granted a royal pardon by King Norodom Sihanouk in 1996 in exchange for his defection to the government. Pol Pot died in 1998 shortly after he was placed in house arrest by his ex-deputy successor "the Butcher" Ta Mok.

Pol Pot was defended by Hope R. Stevens, a lawyer, political and civic activist, and businessman. As the Co-chairperson of the National Conference of Black Lawyers of the United States and Canada," he appeared as the defense counsel during the trial in absentia of Pol Pot and Ieng Sary at the People's Revolutionary Tribunal (Cambodia) held by the Vietnamese-backed People's Republic of Kampuchea in Phnom Penh in 1979. Stevens was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his public service in fighting for self-determination for Caribbean Islands such as his native St. Kitts-Nevis.

The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (French: Chambres extraordinaires au sein des tribunaux cambodgiens) commonly known as the Cambodia Tribunal or Khmer Rouge Tribunal, was a court established to try the senior leaders and the most responsible members of the Khmer Rouge for alleged violations of international law and serious crimes perpetrated during the Cambodian genocide. Although it was a national court, it was established as part of an agreement between the Royal Government of Cambodia and the United Nations, and its members included both local and foreign judges.

The remit of the Extraordinary Chambers extended to serious violations of Cambodian penal law, international humanitarian law and custom, and violation of international conventions recognised by Cambodia, committed during the period between 17 April 1975 and 6 January 1979. This includes crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide. The chief purpose of the tribunal as identified by the Extraordinary Chambers was to provide justice to the Cambodian people who were victims of the Khmer Rouge regime's policies between April 1975 and January 1979. However, rehabilitative victim support and media outreach for the purpose of national education were also outlined as primary goals of the commission.

In 1997 the Cambodian government asked for the UN's assistance in setting up a genocide tribunal. It took nine years to agree to the shape and structure of the court—a hybrid of Cambodian and international laws—before the judges were sworn in, in 2006. The investigating judges were presented with the names of five possible suspects by the prosecution on 18 July 2007.

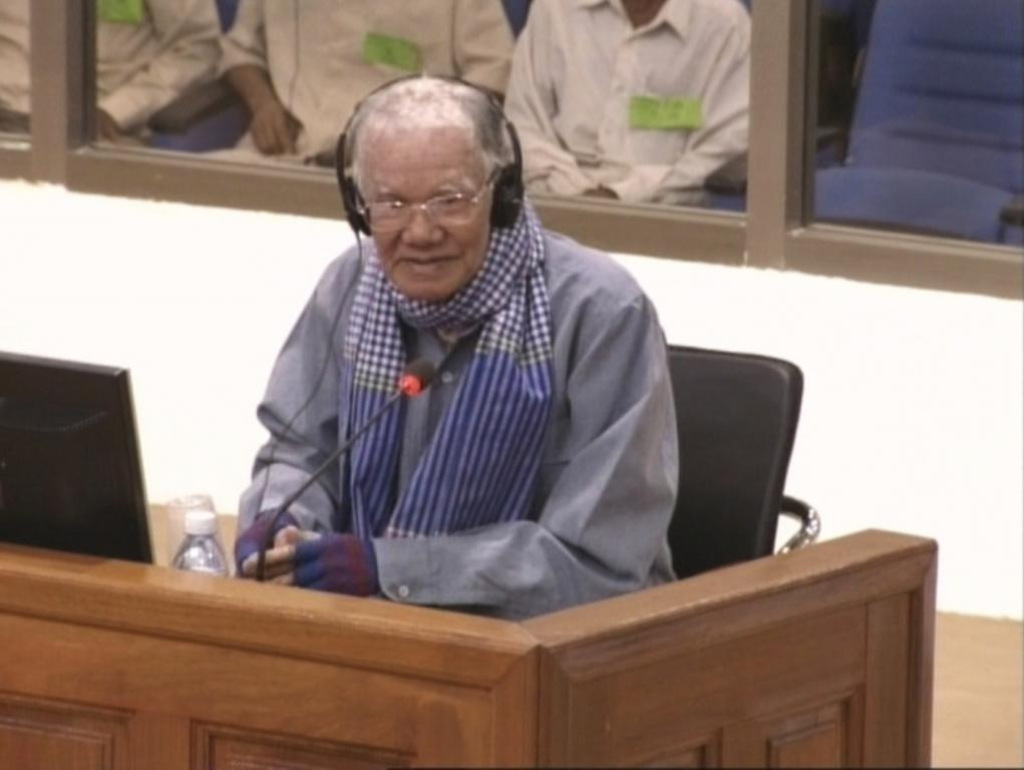

On 19 September 2007 Nuon Chea, second in command of the Khmer Rouge and its most senior surviving member, was charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity. He faced Cambodian and foreign judges at the special genocide tribunal and was convicted on 7 August 2014 and received a life sentence. During the rule of the Khmer Rouge, Nuon Chea, party's chief ideologist, acted as the right-hand man of leader, Pol Pot. Allegations against Nuon Chea included crimes against humanity (murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation imprisonment, torture, persecution on political, racial, and religious grounds), genocide, and serious breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 (willful killing, torture or inhumane treatment, willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health, willfully depriving a prisoner of war or civilian the rights of fair and regular trial, unlawful deportation or unlawful confinement of a civilian).

Nuon Chea joined the Communist Party of Kampuchea (the Khmer Rouge's official name) while studying law at Thammasat University in Bangkok. In 1960, he was appointed Deputy Secretary to oversee the security of the party and the state. His charges included overseeing Phnom Penh's S-21 prison. It is estimated that Nuon Chea is responsible for the death of 1.7 million people during the rule of the Khmer Rouge. In 1998, Nuon Chea reached an agreement with the Cambodian Government which allowed him to live near the Thai border. He was arrested and put into custody in 2007. His case, number 002, has been under investigation since 2007 and hearings began in 2011.

Although Chea is the highest-ranking official to be detained he denies the majority of his involvement in the Khmer Rouge:

“I was president of the National Assembly and had nothing to do with the operation of the government. Sometimes I didn't know what they were doing because I was in the assembly”.

On 7 August 2014, in Case 002/1, the Trial Chamber found Nuon Chea guilty of numerous crimes against humanity and sentenced him to life imprisonment. On 23 November 2016, The Supreme Court Chamber, although reversing some of the convictions, upheld this sentence. On 16 November 2018, in the second case opened against him before the ECCC (Case 002/02), the Trial Chamber found him guilty of genocide against the Vietnamese people and the Cham people. Nuon Chea died on 4 August 2019 while appealing his conviction for genocide against the Vietnamese people and the Cham people in Case 002/2.

The Supreme Court Chamber terminated these remaining proceedings against him on 13 August 2019 but his defense lawyers filed a request before the Supreme Court Chamber arguing that, in absence of any appeal judgment, Nuon Chea should be considered innocent and that trial judgement issued on 16 November 2018 against him should be vacated. On 22 November 2019, the Supreme Court Chamber clarified notably that Nuon Chea's death did not vacate the trial judgment against him and that, although the presumption of innocence applies at the appeal stage, it does not equate to post mortem finding of not guilty.

Ieng Sary was arrested on 12 November 2007. Sary allegedly joined the Khmer Rouge in 1963. Before he studied in France where he joined the French Communist Party and upon his return to Cambodia, he joined CPK. When the Khmer Rouge took control in 1975, Ieng became the Deputy Prime Minister for Foreign Affairs. When the regime fell in 1979, Ieng fled to Thailand and was convicted of genocide and sentenced to death by the People's Revolutionary Tribunal of Phnom Penh. Ieng remained a member of the Khmer Rouge government in exile until 1996 when he was granted a royal pardon for his conviction and royal amnesty for this outlawing of the Khmer Rouge.

Sary is alleged responsible (through his acts or omissions) for planning, instigating, ordering, aiding/abetting, or overseeing of the crimes of the Khmer Rouge between 1975 and 1979. Allegations against Ieng Sary include crimes against humanity, genocide and breaches of the Geneva Convention. Ieng Sary died in March 2013 while the case against him was still ongoing and no verdict had yet been handed over.

Ieng Thirith, wife of Ieng Sary and sister-in-law of Pol Pot, was a senior member of the Khmer Rouge. She studied in France and was the first Cambodian to receive a degree in English. Upon her return to Cambodia, she joined CPK and was allegedly appointed Minister of Social Affairs in Democratic Kampuchea. Thirith remained with the Khmer Rouge until her husband, Ieng Sary, was pardoned by the Cambodian government in 1998. After, she and Sary lived together near Phnom Penh until both were arrested by Cambodian police and tribunal officials on 12 November 2007.

Thirith is allegedly responsible for the planning, instigating, and aiding/abetting the crimes of the Khmer Rouge against Cambodians during the time of Khmer Rouge control. Allegations against Thirith include crimes against humanity, genocide and breaches of the Geneva Convention. In November 2011, Ieng Thirith was found to be mentally unfit to stand trial, due to Alzheimer's disease. Ieng Thirith died in August 2015.

On 26 July 2010 Kang Kek Iew (also spelled Kaing Guek Eav) aka Comrade Duch, director of the S-21 prison camp, was convicted of crimes against humanity and grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, he was sentenced to 35 years' imprisonment. His sentence was reduced to 19 years, as he had already spent 11 years in prison. On 2 February 2012, his sentence was extended to life imprisonment by the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. He died on 2 September 2020.

Kang Kek Iew was the first of the five brought before the tribunal; his hearings began on 17 September 2009 and concluded on 27 November 2010. Seven areas of relevance resurfaced frequently during Kang Kew Lew's trial: issues relating to M-13, the establishment of S-21 and the Takmao prison, the implementation of CPK policy at S-21, armed conflict, the functioning of S-21, the establishment and functioning of S-24; and issues relating to character of Kang Kek Iew himself.

“The crimes committed by Kaing Guek Eav were undoubtedly among the worst in recorded human history. They deserve the highest penalty available to provide a fair and adequate response to the outrage these crimes invoked in victims, their families and relatives, the Cambodian people, and all human beings. The Co-Prosecutors did not exaggerate when they referred to S-21 as the “factory of death.” Kaing Guek Eav commanded and operated this factory of death for more than three years. He is responsible for the merciless termination of at least 12,272 individuals, including women and children”.

His lieutenant Mam Nay, the feared leader of the interrogation unit of the Santebal, gave testimony on 14 July 2009 and, although implicated in hands-on torture and execution along with Duch, he was not charged. Initially, Kang Kek Iew was sentenced to 35 years imprisonment. However, this was reduced owing to his illegal detention by the Cambodian Military Court between 1999 and 2007 and time already spent in the custody of the ECCC. The sentence was extended to life in prison on appeal

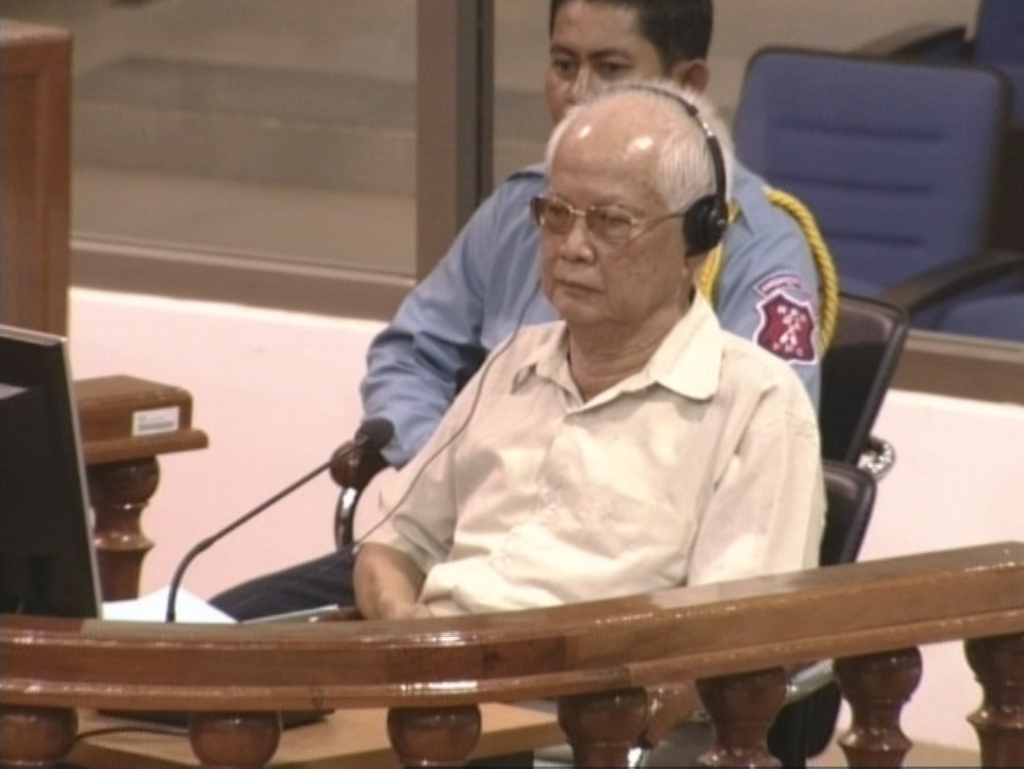

Khieu Samphan acted as one of the Khmer Rouge's most powerful officials. Before joining the Khmer Rouge, Khieu Samphan was Secretary of State for Trade for the Sihanouk regime in 1962. Under threat of Sihanouk's security forces, Samphan went into hiding in 1969 and emerged as a member of the Khmer Rouge in the early 1970s. He was appointed Democratic Kampuchea's Head of State and succeeded Pol Pot as leader of the Khmer Rouge in 1987. Khieu Samphan pledged allegiance to the Cambodian government in 1998 and left the Khmer Rouge.

He was arrested on 12 November 2007 on the allegations of the commission of crimes against humanity, genocide and violations of the Geneva Conventions. On August 7, 2014, he was found guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced to life imprisonment, in Case 002/1. The sentence was upheld on appeal. In the second case against him, the Trial Chamber found him guilty of the crime of genocide against the Vietnamese people on 16 November 2018. His appeal against this conviction for genocide was rejected on 22 September 2022, with the guilty verdicts of genocide, crimes against humanity, and grave breaches of the Geneva Convention confirmed.

The investigation in Case 003 focuses on the crimes committed by Meas Muth (alias "Achar Nen"), high-ranking member of the Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea (RAK) during the period from 17 April 1975 to 6 January 1979. Meas Muth was the Commander of Division 164, the largest division of the RAK that included the command of entire Navy, was a reserve member of the General Staff Committee and was the Secretary of the Kampong Som Autonomous Sector (which reported directly to the Party Center).

Center for Justice & Accountability represents 76 Civil Party applicants to the Case 003 proceedings. It was headquartered in the Kampong Saom area, with bases in several ports along the sea coast and on islands in the Gulf of Siam. Meas Muth had command of 10 000 forces. As Navy Commander, Meas Muth also delivered prisoners to the execution sites, including the infamous S-21 prison. Meas Muth is also blamed for the deaths of 11 Westerners who were seized after their boats strayed into Cambodian waters. They were arrested and sent to S-21 where they perished.

On 18 November 2018, the Co-Investigating Judges issues their Closing Orders. The National Co-Investigating issued an order dismissing all the charges against Meas Muth on the ground that he is not one of the most responsible for the crimes committed during the Khmer Rouge regime. Conversely, the International Co-Investigating Judge found Meas Muth to be one of the most responsible for war crimes and genocide and indicted him under the charges of genocide of the Thai and Vietnamese, crimes against humanity, war crimes and homicide under the 1956 Cambodian Penal Code. As Navy commander Meas Muth had sufficient authority and culpability to be considered “most responsible".

When the Khmer Rouge took control of Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975, Yim Tith was appointed as the party secretary for Kirivong district (in Sector 13). During the regime's power, Yim Tith rose to the position of Sector 13 secretary (until June 1978) and later became secretary of the North West Zone Sectors 1, 3 and 4. He is believed to responsible for crimes committed by Khmer Rouge cadres in Takeo Province from 1975 to 1978, in Pursat Province in 1978 to 1979 and later in Battambang Province in 1978 to 1979. He targeted Khmer Krom and Vietnamese communities for total elimination.

On 28 June 2019, the Co-Investigating Judges issues their closing orders. The National Co-Investigating issued an order dismissing all the charges against Yim Tith on the ground that he is not one of the most responsible for the crimes committed during the Khmer Rouge regime. Conversely, the International Co-Investigating Judge found Yim Tith to be one of the most responsible notably for the genocide of the Khmer Krom, crimes against humanity, war crimes as well as domestic offences under Cambodian law.

Former Khmer Rouge navy commander Meas Muth remains free despite the issuance of 2 outstanding arrest warrants. These arrest warrants have not been acted upon by police officials and Muth continues to live in relative peace in Battambang province, while his Case 003, as it is known, continues to be opposed by Prime Minister Hun Sen. The three Cambodian judges on the panel have defended their opposition by stating that an arrest "in Cambodian society, is regarded as humiliating and affecting Meas Muth's honour, dignity and rights substantially and irremediably." Muth is charged with homicide and crimes against humanity, allegedly committed in a number of different locations around the country and its islands.

“After international co-investigating Judge Laurent Kasper-Ansermet (Swiss) left his job unexpectedly, it cast more doubt on the court's ability to pursue more cases such as Case 003 and 004 against the ailing Khmer Rouge leaders.”.

ECCC's prosecution was suggested to drop case 004 in return to get Cambodian judges to agree to proceed with Case 003 as Meas Muth was directly responsible for Khmer Rouge Navy and some districts. Conviction of Meas Muth would represent significant portion of Khmer Rouge misplaced regime as a whole. The Cambodian Prime Minister and dictator Hun Sen who has been in power since 1985, himself a former Khmer Rouge soldier, does not want himself or his subordinates involved in additional trials, as more truth would come to light on lower level Khmer Rouge cadres who are now serving in the government.

With no other living senior members of the Khmer Rouge to indict, the tribunal concluded in December 2022, with just three convictions in all.

There are many criticisms involving the ECCC. For instance there has been significant controversy surrounding the closings of Case 003 and Case 004. Many international critics say these closings stem from a reluctance by the Cambodian government to try Khmer Rouge officials who managed to switch alliances towards the end of the conflict. Furthermore, the ECCC has been criticised for its general stagnancy in relation to its finances. In financing the tribunal, the Cambodian government and the United Nations are both responsible for managing the cost of operations of the ECCC. Between 2006 and 2012, $173.3 million were spent on the ECCC. Out of the $173.3 million, Cambodia has contributed $42.1 million, while the United Nations has donated the other $131.2 million.

For the year 2013, Cambodia has a budget of $9.4 million to spend, while the United Nations has $26 million, making the total budget for that year $35.4 million. However, as of 2014, the ECCC had cost over $200,000,000, in which, at that point, only one case has been completed. Many in the international committee demand an outside committee to review the failures of the ECCC thus far. In accordance, many urge countries such as Japan, Germany, France, the United States, and the United Kingdom to stop financing the ECCC until it becomes a more transparent and independent court.

The court has also been criticised for its rejections of victim applications. A victim applying to participate in Case 003 was rejected because the judges claimed her psychological harm to be "highly unlikely to be true" and through a narrow definition of "direct victim", determined her an indirect victim in the case. The Open Society Justice Initiative calls for the UN to investigate the proceedings of the ECCC. A trial monitor for the OSJI claimed that the recent proceedings "don't meet basic requirements or adhere to international standards or even comply with the court's own prior jurisprudence." In late February 2012, the court requested another $92 million to cover its operating cost for 2012 and 2013.