The Great Famine, also known as the Great Hunger, the Famine (mostly within Ireland) or the Irish Potato Famine (mostly outside Ireland), was a period of mass starvation and disease in Ireland from 1845 to 1852.

White Diaspora

Some called it Colonisation, but we know of it as White Diaspora, a migration of indigenous European people covertly dislodged from their ancestral homelands by a succession of unnatural disasters, enforced by an orchestrated, insidious tyranny of ethnic genocide.

- Proclamation 1625

- Great Famine of Ireland

- Confederation War

- Highland Clearances

- Compact Cities

- Telescopic Philanthropy

- Penal Colonies

- White Slavery

Proclamation 1625

When one thinks of slavery in America, the only thought that comes to mind is Africans picking cotton in the fields of America. What many Americans don’t know is that the Irish preceded the Africans as slaves in the early British colonies of America and the West Indies. They toiled in the tobacco fields of Virginia and Maryland and the sugar cane fields of Barbados and Jamaica. King James I’s Proclamation ordering the Irish be placed in bondage opened the door to wholesale slavery of Irish men, women and children. This was not indentured servitude but raw, brutal mistreatment that included being beaten to death.

The Irish were forced from their land, kidnapped, fastened with heavy iron collars around their necks, chained to 50 other people and held in cargo holds aboard ships as they were transported to the American colonies. The Irish and African slaves were housed together and were forced to mate to provide the plantation owners with the additional slaves they needed. The British abolished slavery in 1833. This act emancipated the Irish slaves in the British West Indies. America abolished slavery in 1865. None of this freed the Irish to the degree they wanted because America had classified them as ‘colored’ and treated them accordingly.

Great Famine of Ireland

The Great Famine (Irish: an Gorta Mór), also known as the Great Hunger, the Famine (mostly within Ireland) or the Irish Potato Famine (mostly outside Ireland), was a period of mass starvation and disease in Ireland from 1845 to 1852. With the most severely affected areas in the west and south of Ireland, where the Irish language was dominant.

The worst year of the period was 1847, known as “Black '47". During the Great Hunger, about 1 million people died and more than a million fled the country, causing the country's population to fall by 20%–25%, in some towns falling as much as 67% between 1841 and 1851. Between 1845 and 1855, no less than 2.1 million people left Ireland, primarily on packet ships but also steamboats and barks—one of the greatest mass exoduses from a single island in history.

In the 40 years that followed the Acts of Union, successive British governments grappled with the problems of governing a country which had, as Benjamin Disraeli stated in 1844, “a starving population, an absentee aristocracy, an alien established Protestant church, and in addition, the weakest executive in the world”. One historian calculated that, between 1801 and 1845, there had been 114 commissions and 61 special committees enquiring into the state of Ireland, and that “without exception their findings prophesied disaster; Ireland was on the verge of starvation, her population rapidly increasing, three-quarters of her labourers unemployed, housing conditions appalling and the standard of living unbelievably low”.

“It would be impossible adequately to describe the privations which they [the Irish labourer and his family] habitually and silently endure … in many districts their only food is the potato, their only beverage water … their cabins are seldom a protection against the weather … a bed or a blanket is a rare luxury … and nearly in all their pig and a manure heap constitute their only property.”

Landlords were responsible for paying the rates of every tenant whose yearly rent was £4 or less. Landlords whose land was crowded with poorer tenants were now faced with large bills. Many began clearing the poor tenants from their small plots, and letting the land in larger plots for over £4, which then reduced their debts. In 1846, there had been some clearances, but the great mass of evictions came in 1847. According to James S. Donnelly Jr., it is impossible to be sure how many people were evicted during the years of the famine and its immediate aftermath. It was only in 1849 that the police began to keep a count, and they recorded a total of almost 250,000 persons as officially evicted between 1849 and 1854.

“Seven hundred human beings were driven from their homes in one day and set adrift on the world, to gratify the caprice of one who, before God and man, probably deserved less consideration than the last and least of them ... The horrid scenes I then witnessed, I must remember all my life long. The wailing of women—the screams, the terror, the consternation of children—the speechless agony of honest industrious men—wrung tears of grief from all who saw them. I saw officers and men of a large police force, who were obliged to attend on the occasion, cry like children at beholding the cruel sufferings of the very people whom they would be obliged to butcher had they offered the least resistance. The landed proprietors in a circle all around—and for many miles in every direction—warned their tenantry, with threats of their direct vengeance, against the humanity of extending to any of them the hospitality of a single night's shelter … and in little more than three years, nearly a fourth of them lay quietly in their graves”.

“The fight in Ireland has been one for the soul of a race - that Irish race which with seven centuries of defeat behind it still battled for the sanctity of its dwelling place.”

Many Irish people, notably Mitchel, believed that Ireland continued to produce sufficient food to feed its population during the famine, and starvation resulted from exports. According to historian James Donnelly, “the picture of Irish people starving as food was exported was the most powerful image in the nationalist construct of the Famine”. The historian Cecil Woodham-Smith wrote in The Great Hunger: Ireland 1845–1849 that no issue has provoked so much anger and embittered relations between England and Ireland “as the indisputable fact that huge quantities of food were exported from Ireland to England throughout the period when the people of Ireland were dying of starvation”.

“With starvation at our doors, grimly staring us, vessels laden with our sole hopes of existence, our provisions, are hourly wafted from our every port. From one milling establishment I have last night seen not less than fifty dray loads of meal moving on to Drogheda, thence to go to feed the foreigner, leaving starvation and death the sure and certain fate of the toil and sweat that raised this food. ”

Confederation War

In 1641, Ireland’s population was 1,466,000 and in 1652, 616,000. According to Sir William Petty, 850,000 were “wasted by the sword, plague, famine, hardship and banishment during the Confederation War 1641-1652.” At the end of the war, vast numbers of Irish men, women and children were forcibly transported by the English government. In 1655, when England captured Jamaica from Spain, Oliver Cromwell needed to populate their new colony. Some were convicts, many indentured servants and very few of the deportees had committed any great crimes. Deportation “beyond the sea, either within His Majesty’s dominions or elsewhere outside His Majesty’s Dominions” was one of their methods of dealing with the Irish issue and, more importantly, populating England’s new acquisition.

One man whose crime was to harbour a priest was imprisoned, while his three daughters were sent to Jamaica. In order to prevent the new arrivals forming communities the three girls were sent to different corners of Jamaica. Large numbers of the Irish exiles died from heat and diseases. It was thought that the Irish would have a better chance of survival if they were introduced to the climate at a young age. Cromwell then sent 2,000 children between the age of 10 and 14 years. Migration to Jamaica continued through the 17th century. The term Redleg was coined. The fair skin of the Irish frazzled beneath the Caribbean sun.

Some Irish emigrated "willingly", especially during the sugar boom, but few had any of idea of what to expect. In 1841 a Jesuit priest recorded the arrival of a ship from Limerick, “They landed in Kingston wearing their best clothes and temperance medals.” They laid their roots and contributed to Jamaica’s changing island and motto, “Out of many, one people.” Some Irish acquired land and slaves. Names like O’Hara and O’Connor were recorded in 1837 during the compensation hearings when slaves were freed and their owners remunerated. The strong Irish influence is seen in place names, Irish Town, Clonmel, Dublin Castle, Sligoville, Belfast, Athenry and Kildare.

Highland Clearances

Highland Clearances, (dubbed as Scottish Agricultural Revolution) was the forced eviction of inhabitants of the Highlands and western islands of Scotland, beginning in the mid-to-late 18th century and continuing intermittently into the mid-19th century. The removals cleared the land of people under the guise of allowing the introduction of sheep pastoralism. In the first phase, clearance resulted from “agricultural improvement”, driven by the need for landlords to increase their income (many landlords had crippling debts, with bankruptcy playing a large part in the history).

“His later years were spent in pathetic loneliness. He had seen his parish almost emptied of its people. Glen after glen had been turned into sheep-walks, and the cottages in which generations of gallant Highlanders had lived and died were unroofed, their torn walls and gables left standing like mourners beside the grave, and the little plots of garden or of cultivated enclosure allowed to merge into the moorland pasture. He had seen every property in the parish change hands, and though, on the whole, kindly and pleasant proprietors came in place of the old families, yet they were strangers to the people, neither understanding their language nor their ways. …At one stroke of the pen, ‟ he said to me, … “two hundred of the people were ordered off. …The sense of change was intensely saddened as he went through his parish and passed ruined houses here, there, and everywhere.”

The second phase (c.1815–20 to 1850s) involved overcrowded crofting communities from the first phase that had lost the means to support themselves, through famine and/or collapse of industries that they had relied on (such as the kelp trade), as well as continuing population growth. This is when “assisted passages” were common, when landowners paid the fares for their tenants to emigrate.

Tenants who were selected for this had, in practical terms, little choice but to emigrate. The Highland Potato Famine struck towards the end of this period, giving greater urgency to the process. Emigration was part of Highland history before and during the clearances, but reached its highest level after them. During the first phase of the clearances, emigration could be considered a form of resistance to the loss of status being imposed by a landlord's social engineering.

The subject matter of these clearances was largely ignored by academic historians until the publication of a best-selling history book by John Prebble in 1963 attracted worldwide attention to his view that Highlanders had been forced into tragic exile by their former chieftains turned brutal landlords.

Historians generally disputed this work as over-simplification, but other authors went further and elaborated that the clearances were an equivalent to genocide or ethnic cleansing and/or that British authorities in London played a major, persistent role in carrying them out. In particular, popular remembrance of the Highland clearances is sometimes intertwined with the comparatively short-lived but significant reprisals that followed the failed Jacobite rebellion of 1745.

First phase clearances involved break up of the traditional townships (bailtean), the essential element of land management in Scottish Gaeldom. These multiple tenant farms were most often managed by tacksmen. To replace this system, individual arable smallholdings or crofts (marginalisations) were created, with shared access (socialism) to common grazing.

This process was often accompanied by moving the people from the interior straths and glens to the coast, where they were expected to find employment in, for example, the kelp or fishing industries. The properties they had formerly occupied were then converted into large sheep holdings. Essentially, therefore, this phase was characterised by relocation rather than outright expulsion.

The second phase of clearance started in 1815–20, continuing to the 1850s. It followed the collapse or stagnation of the wartime industries and the continuing rise in population. In the second phase, landlords moved to the more Draconian policy of expelling people from their estates. This was increasingly associated with 'assisted emigration', in which landlords cancelled rent arrears and paid the passage of the 'redundant families' in their estates to North America and, in later years, also to Australia. The process reached a climax during the Highland Potato Famine of 1846–55.

A wave of mass emigration came in 1792, known to Gaelic-speaking Highlanders as Bliadhna nan Caorach (“Year of the Sheep”). Landlords had been clearing land to establish sheep farming. In 1792 tenant farmers from Strathrusdale led a protest by driving more than 6,000 sheep off the land surrounding Ardross. This action, commonly referred to as the “Ross-shire Sheep Riot”, was dealt with at the highest levels in the government; the Home Secretary Henry Dundas became involved. He had the Black Watch mobilised; it halted the drive and brought the ringleaders to trial.

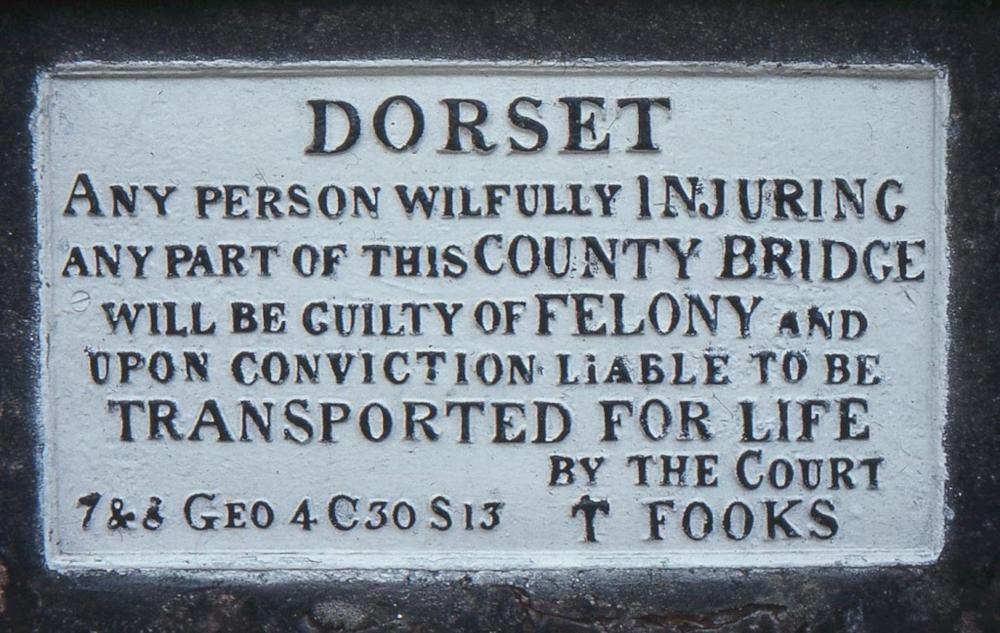

Inverness County Sheriff Court Records reveal the punishments ordered for six men accused of driving sheep away:

They were Hugh Breck MacKenzie, John Aird, Malcolm Ross, Donald Munro, Alexander MacKay and William Cunningham. MacKenzie and Aird were both ordered to be transported for seven years “beyond the seas to such places as His Majesty shall appoint”. If they returned to Britain in those seven years, they were to be sentenced to death. Mackay and Munro were to be banished from Scotland for the rest of their lives.

Dissidents were relocated to poor crofts. Others were sent to small farms in coastal areas, where farming could not sustain the population, and they were expected to take up fishing as a new trade. In the village of Badbea in Caithness, the weather conditions were so harsh that, while the women worked, they had to tether their livestock and their children to rocks or posts to prevent them from being blown over the cliffs. Other crofters were transported directly to emigration ships, bound for North America or Australia.

“these manifold unheard-of judgements continued seven years, not always alike, but the seasons, summer and winter (were) so cold and barren, and the wonted heat of the sun so much withholden that it was discernible upon the cattle, flying fowl and insects decaying, seldom a fly or a cleg was to be seen ; our harvests (were) not in the ordinary months ; many were shearing in November and December, some in January and February ; many contracted their deaths and lost the use of feet and hands working in frost and snow ; and after all, some of it was still standing and rotting upon the ground; much of it was of little use to man or beast, and it had no taste or colour of meal”.

As in Ireland, the potato crop failed in Scotland during the mid-19th century. The ongoing clearance policy resulted in starvation, deaths, and a secondary clearance, when families either migrated voluntarily or were forcibly evicted. There were many deaths of children and the aged. As there were few alternatives, people emigrated, joined the army, or moved to growing urban centres such as Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Dundee in Lowland Scotland and Newcastle upon Tyne and Liverpool in the north of England.

“Oh I am come to the low Countrie, Ochon (eyes), Ochon, Ochrie! Without a penny in my purse, to buy a meal for me.” Ochon! O Donald, oh! Ochon, Occon, Ochrie! [..] Naw woman in the warld wide, Sae wretched now as me”.

Others squatted in Highland towns such as Tobermory, Lochcarron, or Lochaline. In places, some people were given economic incentives to move, but in many instances landlords used violent methods:

“Evictions during the famine were often governed by an undisguised determination to expel the people. In addition, these clearances were unleashed on a population already ravaged by hunger and destitution, and few attempts were made to provide shelter to the dispossessed.”.

After the potato “blight”, it was claimed there were more people than the land could support. The potato famine gave rise to the Highland and Island Emigration Society, which sponsored around 5,000 emigrants to Australia from the affected areas of Scotland It has frequently been asserted that Gaels reacted to the Clearances with apathy and a near-total absence of active resistance from the crofting population.

However, upon closer examination this view is at best an oversimplification, one historian points to more than 50 major acts of resistance to clearances, such as Gaelic communities staving off or even averted removals by accosting law enforcement officials and destroying eviction notices.

Compact Cities

Populations of cities began to condense as people arrived from being driven out from rural areas of Scotland, Ireland, England and Wales. Scotland was written as the worst, although Ireland was clearly suffering greatly.

“I have never seen such a concentration of misery as in this parish," where the people are without furniture, without everything. “I frequently see the same room occupied by two married couples. I have been in one day in seven houses where there was no bed, in some of them not even straw. I found people of eighty years of age lying on the boards. Many sleep in the same clothes which they wear during the day. I may mention the case of two Scotch families living in a cellar, who had come from the country within a few months…. Since they came, they had had two children dead, and another apparently dying. There was a little bundle of dirty straw in one corner, for one family, and in another for the other. In the place they inhabit, it is impossible at noonday to distinguish the features of the human face without artificial light. – It would almost make a heart of adamant bleed to see such an accumulation of misery in a country like this.”.

In the Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, Dr. Hennen reports a similar state of things. From a Parliamentary Report:

“….the house,” says an English journal in an article upon the sanitary condition of the working-people in cities, “are often so close together, that persons may step from the window of one house to that of the house opposite — so high, piled story after story, that the light can scarcely penetrate to the court beneath. In this part of the town there are neither sewers nor any private conveniences whatever belonging to the dwellings; and hence the excrementitious and other refuse of at least 50,000 persons is, during the night, thrown into the gutters, causing (in spite of the scavengers' daily labours) an amount of solid filth and foetid exhalation disgusting to both sight and smell, as well as exceedingly prejudicial to health. Can it be wondered that, in such localities, health, morals, and common decency should be at once neglected? No; all who know the private condition of the inhabitants will bear testimony to the immense amount of their disease, misery, and demoralisation. Society in these quarters has sunk to a state indescribably vile and wretched.... The dwellings of the poorer classes are generally very filthy, apparently never subjected to any cleaning process whatever, consisting, in most cases, of a single room, ill-ventilated and yet cold, owing to broken, ill-fitting windows, sometimes damp and partially underground, and always scantily furnished and altogether comfortless, heaps of straw often serving for beds, in which a whole family — male and female, young and old, are huddled together in revolting confusion. The supplies of water are obtained only from the public pumps, and the trouble of procuring it, of course, favours the accumulation of all kinds of abominations.”.

Glasgow is in many respects similar to Edinburgh, possessing the same wynds, the same tall houses. Of this city, the Artisan observes:

“The working-class forms here some 78 per cent of the whole population (about 300,000), and lives in parts of the city “which, in abject wretchedness, exceed the lowest purlieus of St. Giles' or Whitechapel, the liberties of Dublin, or the wynds of Edinburgh. Such localities exist most abundantly in the heart of the city — south of the Irongate and west of the Saltmarket, as well as in the Calton, off the High Street, etc.– endless labyrinths of narrow lanes or wynds, into which almost at every step debouche courts or closes formed by old, ill-ventilated, towering houses crumbling to decay, destitute of water and crowded with inhabitants, comprising three or four families (perhaps twenty persons) on each flat, and sometimes each flat let out in lodgings that confine — we dare not say accommodate — from fifteen to twenty persons in a single room. These districts are occupied by the poorest, most depraved, and most worthless portion of the population, and they may be considered as the fruitful source of those pestilential fevers which thence spread their destructive ravages over the whole of Glasgow.”.

In Leicester, Derby, and Sheffield, it is no better. Of Birmingham, the article above cited from the Artisan states:

“In the older parts of the town there are many inferior streets and courts, which are dirty and neglected, filled with stagnant water and heaps of refuse. The courts of Birmingham are very numerous in every direction, exceeding 2,000, and comprising the residence of a large portion of the working-classes. They are for the most part narrow, filthy, ill-ventilated. and badly drained, containing from eight to twenty houses each, the houses being built against some other tenement and the end of the courts being pretty constantly occupied by ashpits, etc., the filth of which would defy description. It is but just, however, to remark that the courts of more modern date are built in a more rational manner, and kept tolerably respectable; and the cottages, even in old courts, are far less crowded than in Manchester and Liverpool, the result of which is, that the inhabitants, in epidemic seasons, have been much less visited by death than those of Wolverhampton, Dudley, and Bilston, at only a few miles distance. Cellar residences, also, are unknown in Birmingham, though some few are, very improperly, used as workshops. The low lodging-houses are pretty numerous (somewhat exceeding 400), chiefly in courts near the centre of the town; they are almost always loathsomely filthy and close, the resorts of beggars, trampers, thieves and prostitutes, who here, regardless alike of decency or comfort, eat, drink, smoke and sleep in an atmosphere unendurable by all except the degraded, besotted inmates.”.

J. C. Symons, Government Commissioner for the investigation of the condition of the hand-weavers, describes these portions of the city:

“I have seen human degradation in some of its worst phases, both in England and abroad, but I did not believe until I visited the wynds of Glasgow, that so large an amount of filth, crime, misery, and disease existed in any civilised country. In the lower lodging-houses ten, twelve, and sometimes twenty persons of both sexes and all ages sleep promiscuously on the floor in different degrees of nakedness. These places are, generally, as regards dirt, damp and decay, such as no person would stable his horse in.”.

And in another place

“The wynds of Glasgow house a fluctuating population of between 15,000 and 30,000 persons. This district is composed of many narrow streets and square courts, and in the middle of each court there is a dung-hill. Although the outward appearance of these places was revolting, I was nevertheless quite unprepared for the filth and misery that were to be found inside. In some of these bedrooms we [i.e. Police Superintendent Captain Miller and Symons] visited at night, we found a whole mass of humanity stretched out on the floor. There were often 15 to 20 men and women huddled together, some being clothed and others naked. Their bed was a heap of musty straw mixed with rags. There was hardly any furniture there, and the only thing which gave these holes the appearance of a dwelling was a fire burning on the hearth. Thieving and prostitution are the main sources of income of these people. No one seems to have taken the trouble to clean out these Augean stables, this pandemonium, this nucleus of crime, filth, and pestilence in the second city of the empire. A detailed investigation of the most wretched slums of other towns has never revealed anything half so bad as this concentration of moral iniquity, physical degradation and gross overcrowding…. In this part of Glasgow most of the houses have been condemned by the Court of Guild as dilapidated and uninhabitable — but it is just these dwellings which are filled to overflowing because, by law, no rent can be charged on them.”.

Life was made so miserable and diabolical for our ancestors trapped inside these urban hells, they suffered so greatly, so we could enjoy our the benefits of our world today; that is denounced as white privilege by a socialist gospel of immigrant envy.

They pit indifferences between those who have gone through collectivisation against those who have not collectivised then push miscegenation as the answer, There was no way out for our ancestors, no other option than to board a colonial boat as an indentured servant, face machination inside a workhouse; often begging borrowing and stealing until brandished from their diminished homelands, transported far way to a penal colony; for most never to return.

Telescopic Philanthropy

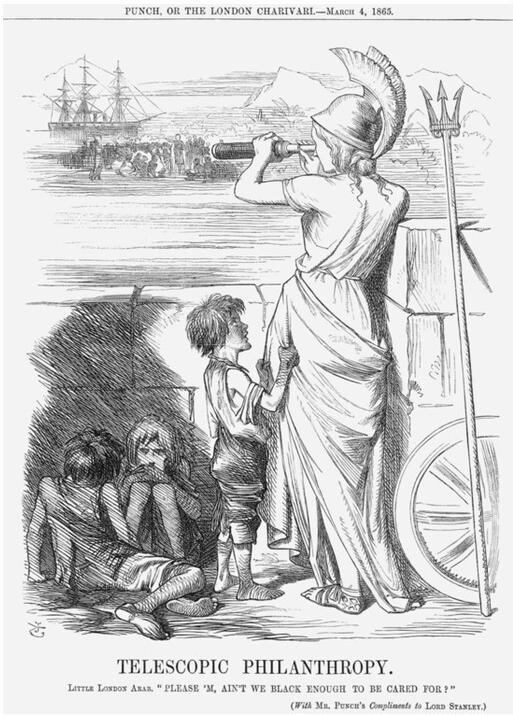

'Telescopic Philanthropy', 1865. 'Little London Arab. Please 'M, Ain't We Black Enough to be Cared For? (With Mr. Punch's Compliments to Lord Stanley.)' In his novel, Bleak House, Dickens had highlighted and satirised the growing numbers of the middle classes who expended much time, effort and money on raising funds to 'civilise' (particularly black) foreign peoples, rather than concentrating on the problems of the poor at home.

This 'telescopic philanthropy' was epitomised by Mrs Jellyby in Bleak House, but here is represented by Britannia who has her eyes fixed so firmly on the distant horizon that she fails entirely to see the three children at her feet who, like Dickens' Jo, represent the estimated 30,000 homeless children living on the streets of London. From Punch, or the London Charivari, March 4, 1865.

Penal Colonies

Penal colony, distant or overseas settlement established for punishing criminals by forced labour and isolation from society. Although a score of nations in Europe and Latin America transported their criminals to widely scattered penal colonies, such colonies were developed mostly by the English, French, and Russians. England shipped criminals to America until the American Revolution and to Australia into the middle of the 19th century.

The initial idea of transporting criminals lay in a law of 1597, entitled:

“An Acte for Punyshment of Rogues, Vagabonds and Sturdy Beggars.”

This law stated that:

“Obdurate idlers shall… be banished out of this Realm.. and shall be conveyed to such parts beyond the seas as shall be… assigned by the Privy Council.”.

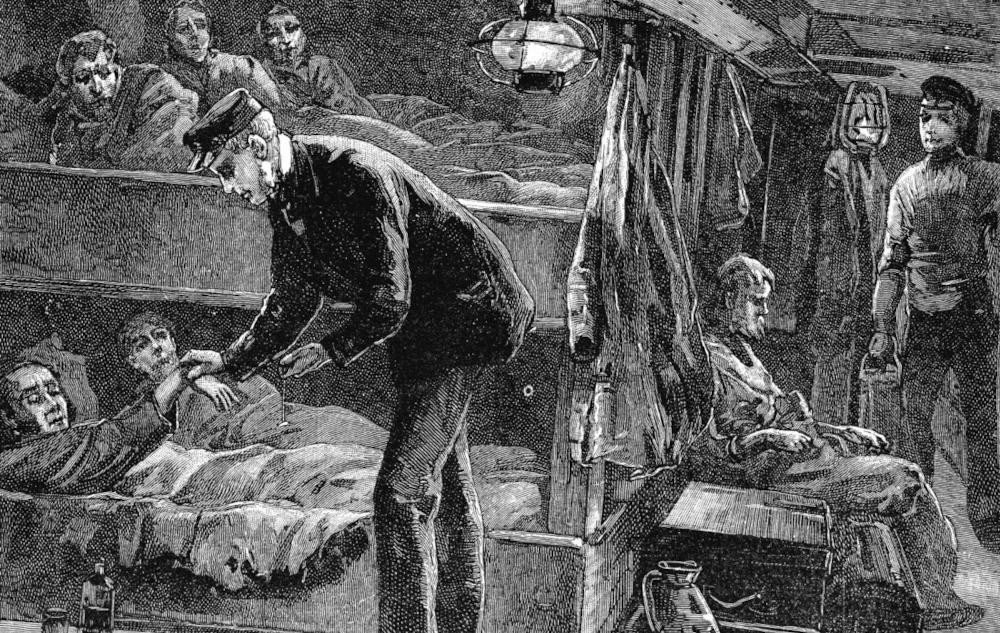

The first fleet of 11 ships, filled with 736 convicts, set sail from England in 1787. They sailed for 8 long months, around Africa’s Cape Hope of Good Hope, into the Indian Ocean. Captain Arthur Phillip, a “tough but fair” naval officer, was in charge of the fleet and with setting up the first penal colony in Australia. The 736 convicts were chained beneath the decks for the entire hellish voyage. While the journey claimed the lives of just 39 prisoners, later trips would see up to a third die along the way.

The following table is an incomplete list is names of transported convicts, many details are missing, including details of convictions:

| Name | Date of Birth | Place of Conviction | Date of Conviction | Sentence | Other Information | Transport Ship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas Baker | c. 1764 | Exeter | 10 January 1786 | 7 Years | Baker was convicted at Exeter for an unrecorded crime, which resulted in him receiving 7 years transportation. A report from the Dunkirk Hulk described Thomas as “troublesome at times.” Baker died between 1788 and September 1792. | Charlotte |

| Mary Cooper | Worcester | 7 Years | ||||

| Elizabeth Bruce | London | 10 January 1787 | 7 Years | Convicted at the Old Bailey (with Elizabeth Anderson) of stealing three linen table-cloths (15s) and two aprons (5s). | ||

| Rebecca Boulton | Lincoln | aka Bolton. Had been in prison for 4 years before the fleet sailed. Considered both mentally ill and in poor physical condition. | Prince of Wales | |||

| Ann Forbes | Kingston | 29 April 1787 | 7 Years | Tried on the 29th day of April 1787. — Ten yards of printed cotton of the value of 20 shillings, of the goods and chattles of James Rollinson in the shop of said James Rollinson, feloniously did steal take and carry away. Guilty, no chattels to be hanged — Reprieved, Transported 7 years. Sent 30 April 1787. | Prince of Wales | |

| Susannah Garth | London | 10 September 1783 | 7 Years | aka Grath. Convicted at the Old Bailey (with Elizabeth Dudgens) for stealing by pickpocketing nine guineas (£9 9s) and one half-guinea (10s 6d). | Friendship and Charlotte | |

| Mary Harrison | London | 19 October 1785 | 7 Years | Convicted at the Old Bailey (with Charlotte Springmore) for wilfully destroying and defacing one cloth cotton gown (10s) of Susannah Edhouse, and for “making an assault on her”. Harrison was said to be a prostitute during the trial. | ||

| John Hill | London | 26 May 1784 | 7 Years | Convicted at the Old Bailey of stealing one linen handkerchief (6s). | ||

| John Hudson | 1775 | London | Dec 1783 | 7 Years | Hudson was 8 years old when convicted in Dec 1783. He was 12 years old when he arrived in Jan 1788. | Friendship |

“Most prisoners were common poachers or thieves, while others were radical Luddites, Catholic Ribbonmen or Scottish Jacobites.”.

Only a small minority of prisoners were hardened criminals convicted of violent crimes. Women made up 15% of the convict population, ships carrying females inevitably became floating brothels. Women were exposed to varying degrees of degradation, with younger women lined up for inspection. The prettiest were taken to the officers’ cabins, while the others were thrown in with the crew.

For the convicts who disembarked in Sydney Cove, that 1st Australia Day were unused to land after 8 months below deck before they stumbled through the cove’s wild alien forest. It was 2 weeks before enough huts could be built for the female convicts to leave the ships.

Between 1790 and 1791 two more fleets arrived in what was now called New South Wales. Convicts were called “transportees”, the average age was 26, and also included children. Over the next 80 years, from that first fleet, more than 160,000 convicts were transported to Australia from England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

After 1868, when convict transfers ended, Australians tried to hide their founder’s legacy, considering it a disgrace and embarrassment. Today, about 20% of Australians are descended from those founding convicts, including many of its most prominent citizens.

White Slavery

In his 2003 book Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500–1800, Ohio State University history professor Robert Davis states that most modern historians minimise the white slave trade. Davis estimates that slave traders from Tunis, Algiers, and Tripoli alone enslaved 1 million to 1.25 million Europeans in North Africa, from the beginning of the 16th century to the middle of the 18th (these numbers do not include the European people who were enslaved by Morocco and by other raiders and traders of the Mediterranean Sea coast).

“More whites were brought as slaves to North Africa than blacks brought as slaves to the United States or to the 13 colonies from which it was formed. White slaves were still being bought and sold in the Ottoman Empire, decades after blacks were freed in the United States.”.

Davis assumes the number of European slaves captured by Barbary pirates remained roughly constant for a 250-year period, stating:

“There are no records of how many men, women and children were enslaved, but it is possible to calculate roughly the number of fresh captives that would have been needed to keep populations steady and replace those slaves who died, escaped, were ransomed, or converted to Islam. On this basis, it is thought that around 8,500 new slaves were needed annually to replenish numbers — about 850,000 captives over the century from 1580 to 1680. By extension, for the 250 years between 1530 and 1780, the figure could easily have been as high as 1,250,000”.

From bases on the Barbary coast, North Africa, the Barbary pirates raided ships travelling through the Mediterranean and along the northern and western coasts of Africa, plundering their cargo and enslaving the people they captured. From at least 1500, the pirates also conducted raids on seaside towns of Italy, Spain, France, England, the Netherlands and as far away as Iceland, capturing men, women and children. On some occasions, settlements such as Baltimore in Ireland were abandoned following a raid, only being resettled many years later. Between 1609 and 1616, England alone lost 466 merchant ships to Barbary pirates.