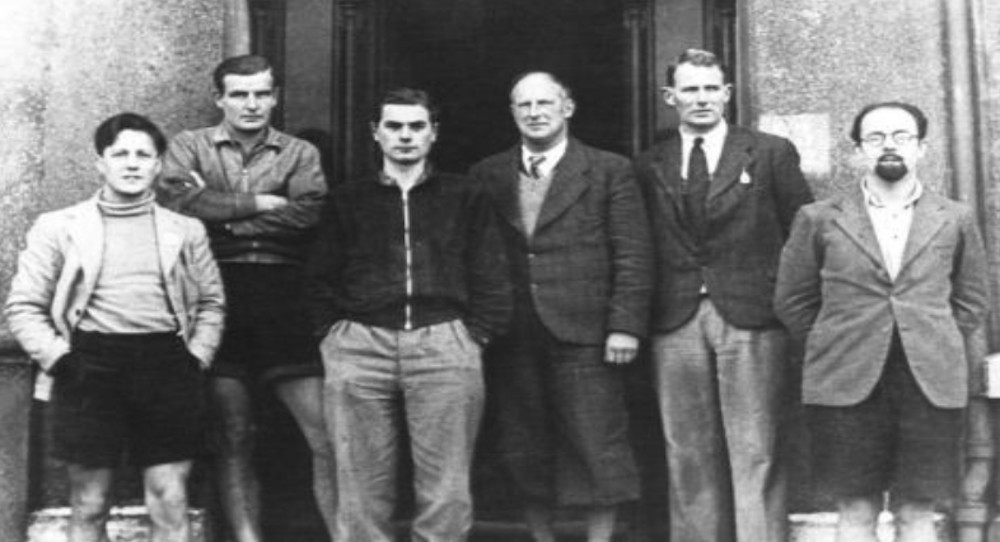

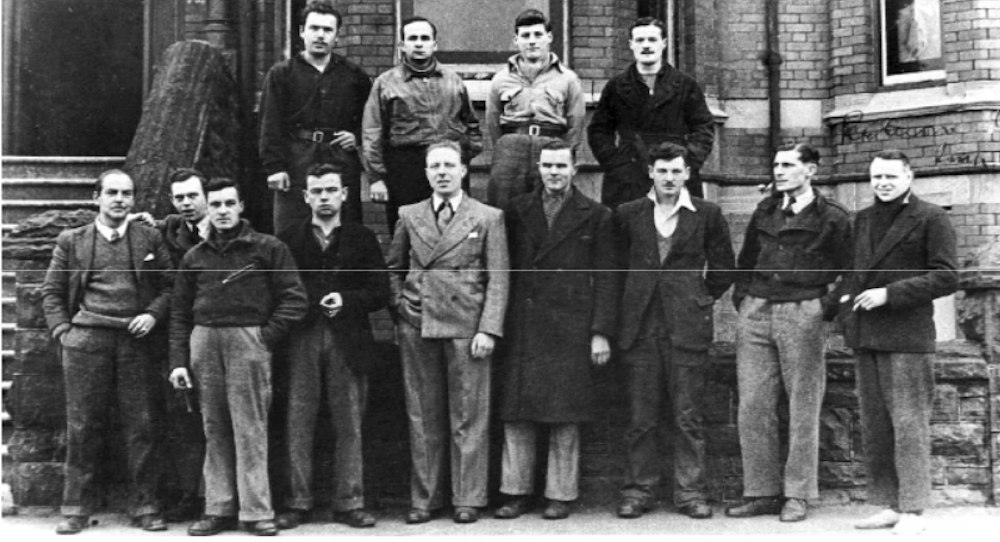

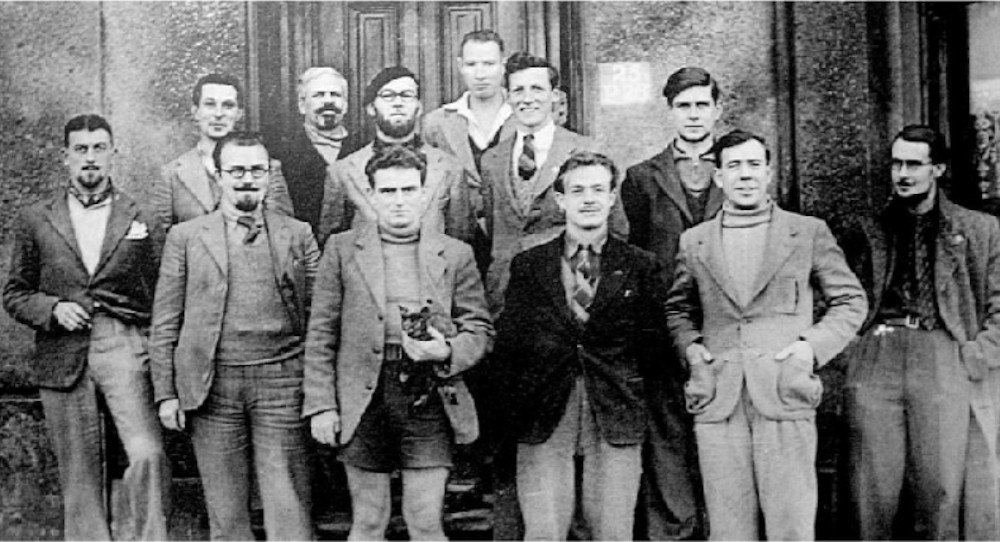

BUF Members interned inside Isle of White Concentration Camp.

Britain's Concentration Camps

Opposing Judea’s initiation of WW2 the British Union of Fascists were locked up under Regulation 18B without committing any crime whatsoever. Known as internment camps these prisons gave inspirational rise to the creation of concentration camp systems both in Poland and Germany.

- Boer War Concentration Camps

- Frongoch Concentration Camp

- British Union of Fascists (Isles of Man)

- Holloway Prison Detainees

- Latchmere House Detainees

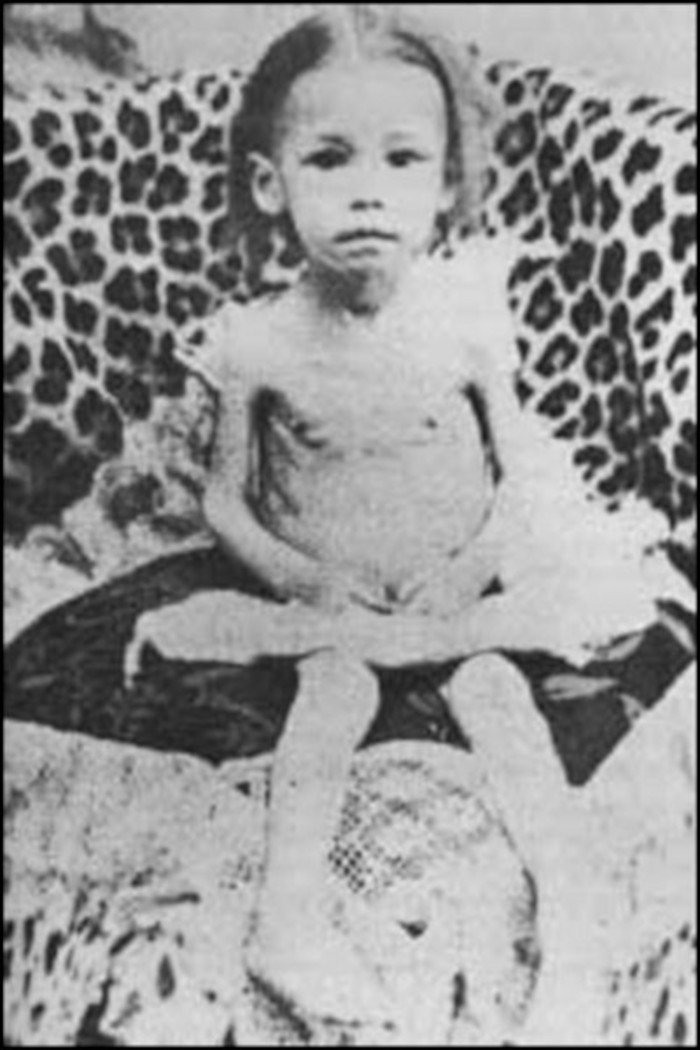

Boer War Concentration Camps

During the Second Boer War (1899–1902) the 28,000 Boer men who were captured as prisoners of war, 25,630 were sent overseas. The vast majority of Boers who remained in the local camps were women and children.

Over 26,000 women and children perished in these concentration camps. The camps were poorly administered from the outset, and they became increasingly overcrowded when Kitchener's troops implemented the internment strategy on a vast scale.

Conditions were terrible for the health of the internees, mainly due to neglect, poor hygiene and bad sanitation. The food rations were meagre and there was a two-tier allocation policy, whereby families of men who were still fighting were routinely given smaller rations than others.

The inadequate shelter, poor diet, bad hygiene and overcrowding led to malnutrition and endemic contagious diseases such as measles, typhoid and dysentery to which the children were particularly vulnerable.

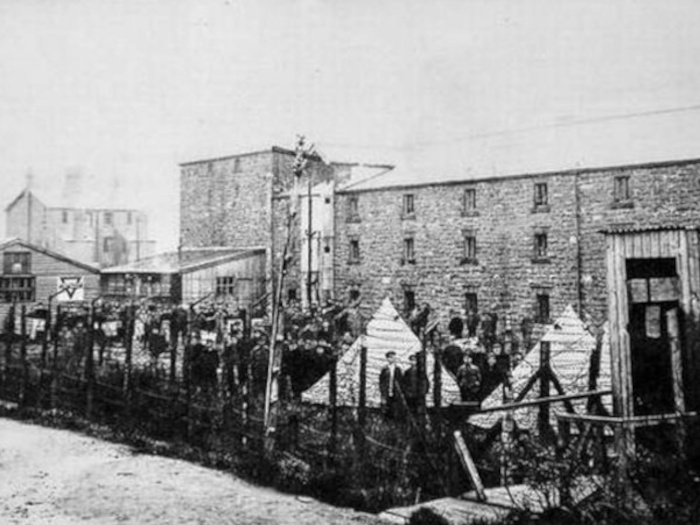

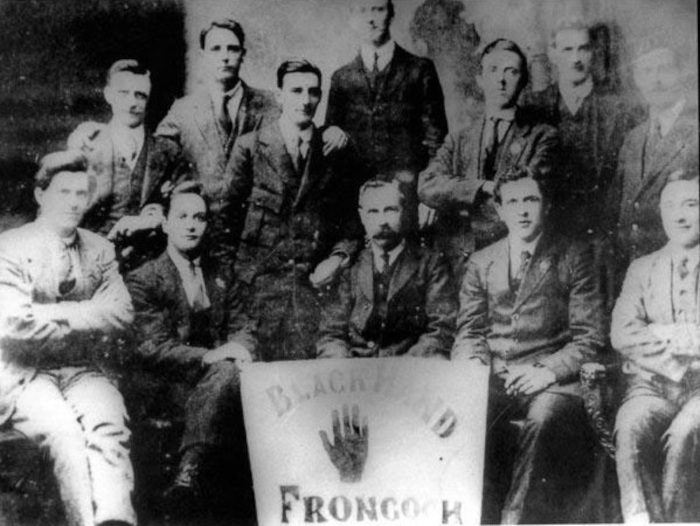

Frongoch Concentration Camp (1916 Easter Rising)

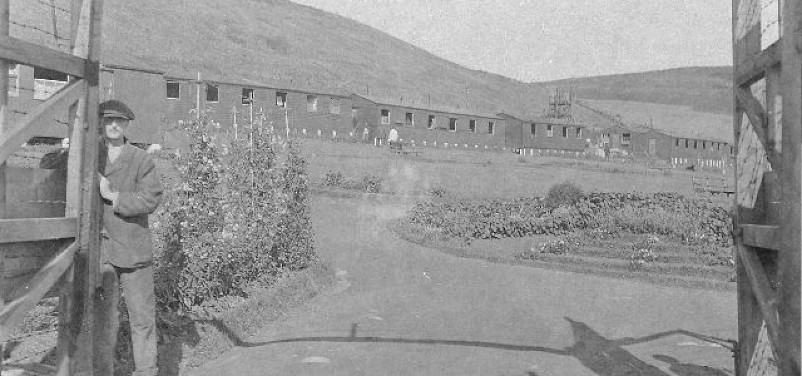

In late months of 1916 British authorities opened a concentration camp in a remote part of Wales to cope with the thousands of Irish political prisoners who had been filling up British prisons. At Frongoch internment camp in North Wales, 1,800 Irish men were held without trial, in the wake of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin.

The prisoners included young farm boys and labourers, but also teachers, poets, artists, authors, trade unionists and military strategists including Michael Collins. With most able-bodied British soldiers away in the first world war, the place was said to be run by the prisoners. The old distillery, a local industry that failed abjectly within five years, was converted into a prison in 1914 to hold German prisoners of war, and then emptied again to hold the Irish.

Under the leadership of Michael Collins, Frongoch Internment Camp became known as the ‘University of Revolution’. Following the failure of the 1916 Easter Rising, Collins and thousands of other rebels were arrested by the British authorities. Many of the uprising’s leaders, such as James Connelly and Patrick Pearse were executed. Collins was fortunate not to be executed, despite having fought at the Dubin GPO, the centre of the uprising. Collins and the other rebels were later imprisoned at Frongoch.

At Frongoch he was one of the organizers of non-cooperation with the British authorities. The camp proved an excellent opportunity for networking and training in guerilla tactics for the republicans. Up to then they had been in small, scattered groups across Ireland. Collins became highly respected among the prisoners and on release went on to become a leader of the newly formed Irish Republican Army (IRA). Their far more successful armed campaign forced the British government to promise to pull out of Ireland.

The stone buildings were damp, freezing, and overrun with rats; a bitter joke among the prisoners was how close the place name was to the Irish word for rat, francach. In 1916 the prisoners, most of whom had never left Ireland before, had only the haziest idea of where they were after being shipped across the Irish Sea, held first in prisons including Knutsford, s they learned of the execution by firing squad of all the surviving signatories of the 1916 proclamation of an Irish Republic, read aloud on the steps of Dublin’s general post office on Easter Monday, many of the prisoners expected the same fate.

Click the following link for a list of detainees interned at Frongoch concentration camp.

British Union of Fascists (Isles of Man)

After military service during the First World War, Mosley was one of the youngest members of parliament, representing Harrow from 1918 to 1924, first as a Conservative, then an independent, before joining the Labour Party. Mosley, shortly before WW2 was focused on pleading for the British to accept Hitler's peace offer of March, but was detained on 23 May 1940, less than a fortnight after Winston Churchill became Prime Minister. Mosley was interrogated for 16 hours by Lord Birkett but never formally charged with a crime, and was instead interned under Defence Regulation 18B.

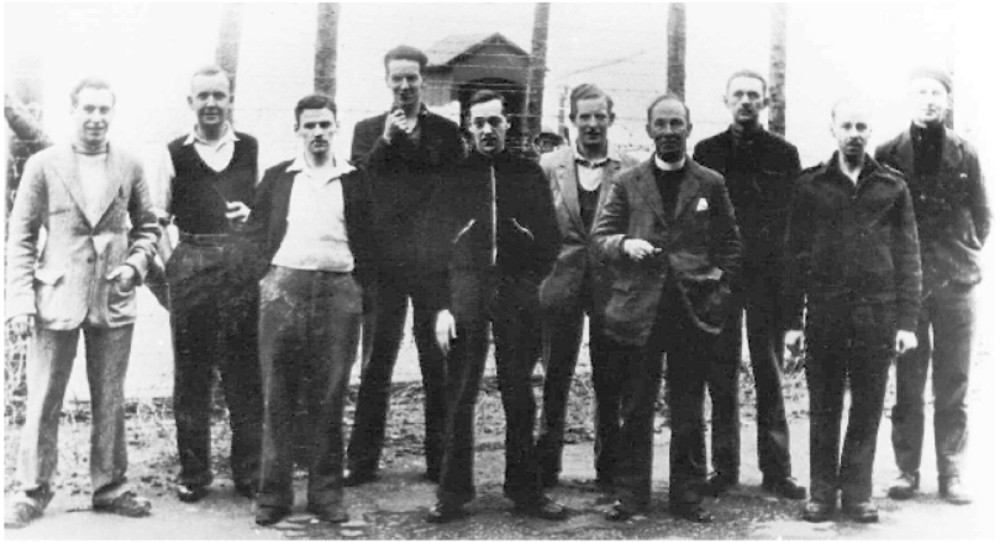

The other most active fascists in Britain met the same fate, resulting in the BUF's practical removal at an organised level from the United Kingdom's political stage. Mosley's wife, Diana, was also interned in June, shortly after the birth of their son (Max Mosley); the Mosleys lived together for most of the war in a house in the grounds of Holloway prison. More than one thousand active members of British Union were detained under Regulation 18B for opposing the Second World War in which 60-million people died. Many of them were imprisoned on the Isle of Man where they were photographed in 1941 by a non-interned BU District Leader serving with the RAF stationed on the Isle of Man. He was smuggled into the Camp with his camera in an empty drum, took these photographs and escaped the same way.

The new Regulation allowed British citizens to be imprisoned without charge, trial or right of judicial appeal if the Home Secretary considered that their continued liberty was not in the national interest during wartime. The main detentions occurred in two phases, September 1939 and May/June 1940, although some 18B orders continued to be issued long after this latter date. Many of these orders were directed against members of the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists.

The list that follows contains the names of those British citizens who are believed to have been detained under Regulation 18B who were, or had been, members of the British Union. It has been compiled from many sources and is probably incomplete. It is also acknowledged that the list may contain inaccuracies, though every effort has been made to avoid these. In some cases, the names are of individuals who are not confirmed as being detained because of British Union membership but where the balance of evidence seems to indicate that they were. These are described as 'Probably British Union'.

The deciding factors concerning who was to be detained under Regulation 18B were far from consistent: many relatively insignificant members were detained whilst some important members escaped detention completely.

Oswald Mosley was interned on the Isle of Man. After imprisonment in the internment camp, the Mosley’s were transferred to Holloway Prison, an adult woman and youth offenders prison in London, which housed Lady Mosley and Oswald Mosley until they were released in November 1943. The Mosley’s were not kept with the general population but had their own house on the grounds separate from the general prison population, with privileges such as the ability to exercise outside not within the set times and the ability to write freely.

Complete list of British Union Fascist Regulation 18b Detainees.

To read / download the full PDF document containing a full list of nine hundred and eighty-five BUF members that were interned, from where the Regulation 18b section of this page is extracted from click here

Holloway Prison Detainees

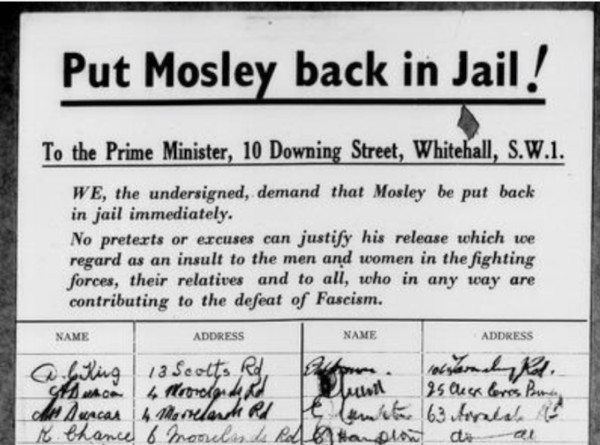

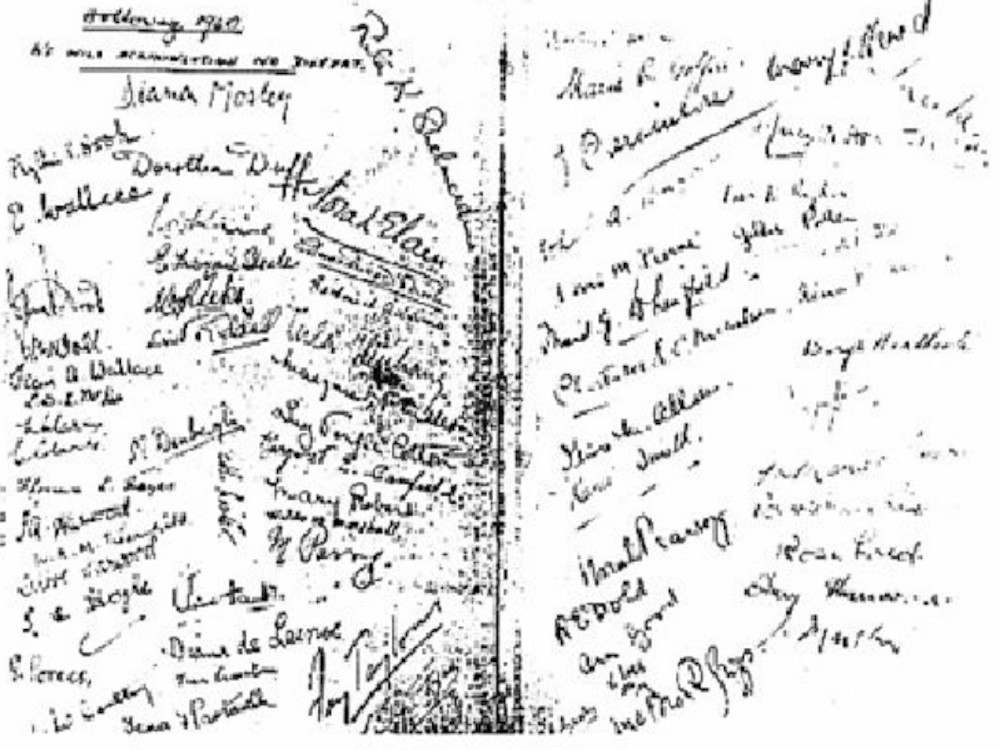

Whilst in Holloway Prison in 1940, Heather Donovan asked other Regulation 18B women, detainees, to autograph some blank pages in a book of Rupert Brooke poems. They signed under the heading 'WE WILL ACKNOWLEDGE NO DEFEAT' and Lady Mosley was the first to add her name.

Notable signatures on these two pages include racing driver Fay Taylour, former suffragette Norah Elam, Lady Domvile and Anne Brock Griggs (Chief Women’s Organiser of BU until February 1940).

WWII Concentration Camps

In June 1940, with a German invasion expected at any moment, Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided to arrest every German and Austrian in the country and send them all to concentration camps. To those who reminded him that many of these people were Jewish refugees, he responded briefly and memorably: “Collar the lot!”. Of course, no one wanted to call these new institutions “concentration camps,” so they renamed them “internment camps” to differentiate them from the concentration camp practice of National Socialist Germany.

Latchmere House Detainees

The following experienced intensive interrogation methods at the Latchmere House Remand Centre, then under MI5 control, at Ham Common, Richmond, Surrey in 1940: Battersby, Compton Domvile, Bryan Donovan, Downing, S Geary, Gill, Eddie Gore, Jimmy Green, Lionel Hirst, Jeeves, King, McKechnie, Peters, Raven Thomson, Sandell, Shelmerdine, Shields, Stuart Smeaton, Stevens, Vaughan-Henry, Watts, E Whinfield, Windsor.

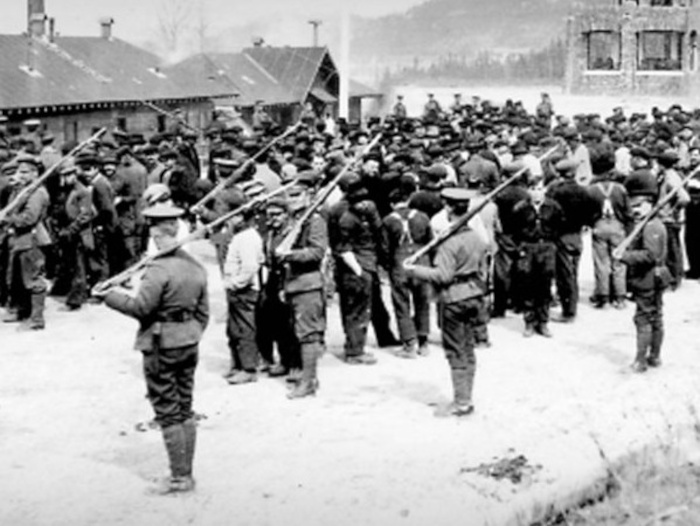

Polish Concentration Camps in Scotland

In 1940, the British government allowed another country to build a running network of concentration camps in Scotland. After the fall of France in 1940, over twenty thousand Polish soldiers were evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk to Britain. The United Kingdom and Poland agreed that they would be dispatched to Scotland, charged with protecting the east coast from the German forces, who had just invaded Norway. In return, the Polish government in exile, led by General Wladyslaw Sikorski, was allowed to conduct their affairs as they saw fit. The British government treated these bases in Scotland as sovereign Polish territory.

General Sikorski feared that other exiled Polish politicians were plotting against him, so he opened a camp at Rothesay, on the Isle of Bute, just thirty miles from Glasgow, for those he worried would threaten his authority. He made no secret of his intentions, explaining at a meeting of the Polish National Council in London on July 18, 1940, “There is no Polish judiciary. Those who conspire will be sent to a concentration camp.” Eventually, Sikorski set up half a dozen camps. Some held political prisoners, including Marian Zyndram-Koscialkowski, former Polish prime minister, and General Ludomil Antoni Rayski, former commander of the Polish Air Force. Others were reserved for “persons of improper moral character,” including homosexuals. Numerous detainees were Jews.

The Rothesay camp was relatively easygoing, intended only to prevent discontented army officers and politicians from working against Sikorski’s interests. While at Rothesay, these dissidents could not be in London attempting to challenge the general’s authority. As the number of camps increased, the newer ones started to look more like the traditional version with barbed wire fences, watchtowers, and brutal guards prepared to shoot prisoners out of hand. Prisoners in camps such as those at Tighnabruich, Kingledoors, and Inverkeithing were certainly mistreated and occasionally murdered.

“On October 29, 1940 a Jewish prisoner named Edward Jakubowsky was shot dead at the camp near Kingledoors. Courts later ruled that the guard who killed him, Marian Przybyski, was using his weapon in the execution of his duties. The British police did not investigate these deaths because the Polish army had complete and unlimited authority over their citizens in Britain.”

As the war continued, some members of parliament became uneasy about the Scottish camps and began asking questions about individual cases, which invariably involved Jewish prisoners. In 1941, Samuel Silverman, the MP for Nelson and Colne, inquired about Benjamin and Jack Ajzenberg, two Jewish brothers who had been arrested by Polish soldiers in London and transported to Scotland. Silverman asked the Secretary of State for war, “How many persons are now detained by the Polish authorities in this country under their powers under the Allied Forces Act?” He received a vague reply: the British government could not afford to alienate their ally at such an important time.

To alleviate fears, the Polish government allowed the press to visit the camp. It quickly regretted this decision: the first prisoner the writers spoke to was another Jew, and the journalists learned that a prisoner had been shot dead by one of the guards the previous week. After World War II ended, the newly elected Labour government put pressure on the Polish authorities to close down their camps, but they stayed open as late as 1946. By that time, the British themselves had begun employing slave labour on an industrial scale, using hundreds of camps across the country to imprison workers.

Surrendered Enemy Personnel

In 1945, Britain held hundreds of thousands of German prisoners at home as well as in Canada, the United States, and North Africa. To use them as slave labour, however, the government would have to strip them of the protections afforded by the Geneva Conventions, which Britain had signed. So, the United Kingdom changed its prisoners’ status from prisoners of war to surrendered enemy personnel. During the war, the Women’s Land Army and schoolchildren donated their time to farming. After peace, it was unlikely that they would continue to engage in back-breaking labour for free. Without an unpaid workforce, the country could not maintain its agricultural output.

In the first postwar year, the United Kingdom brought a staggering number of men from all over the world to work the land. In May 1946, three thousand men a week were arriving in Britain and being sent off to army-protected camps. Between 1945 and 1948, the Nuremberg trials prosecuted Nazi officers for crimes against humanity, including, of course, “compulsory, uncompensated labour.” In 1947, the SS officers who had administered the Third Reich’s slave system were tried, and a number of the defendants were subsequently hanged for their wartime activities. Judge Robert Toms said, “There is no such thing as benevolent slavery. Involuntary servitude, even-tempered by humane treatment, is still slavery.” At the time of this judgment, over three hundred thousand enslaved workers were bringing in the British harvest.

Frith Hill Detention Camp

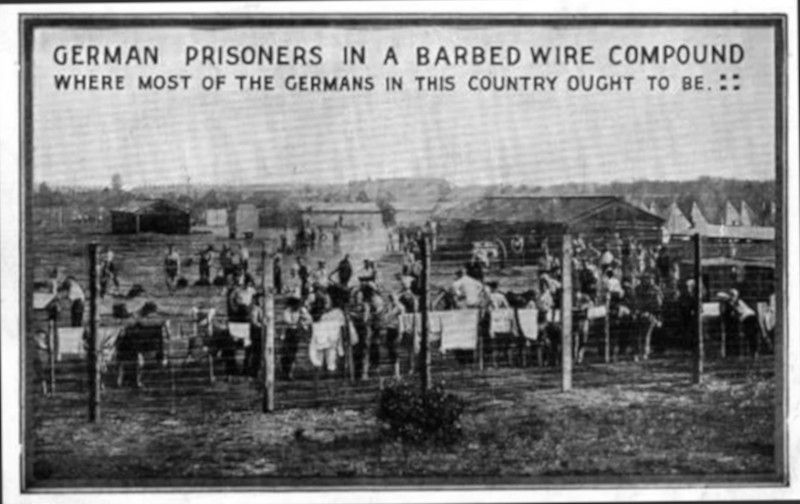

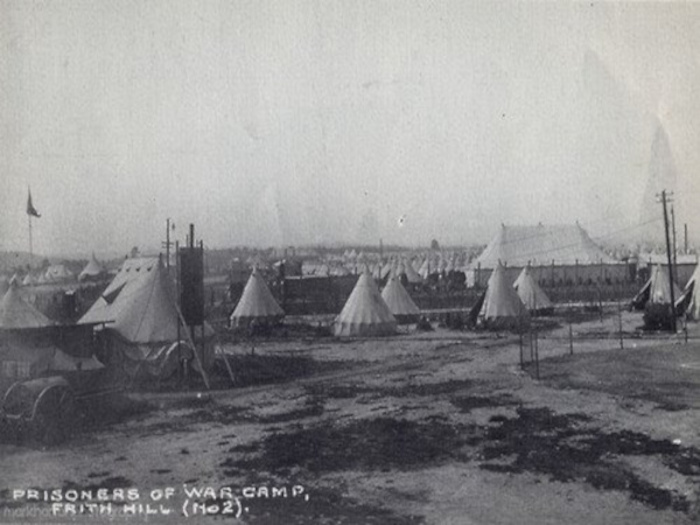

The featured card was posted to Miss Aynsley of County Durham on 4th November 1914, by someone who signed himself 'J.R.' The card was published by the 'Regent Publishing Co., Ltd., London' in ''The War series, No.1856'. A caption at the top of the sepia printed photograph tells us it shows “German prisoners in a barbed wire compound”. We are not told where the prisoners were held, but J.R. knew and tells us on the back of the card. “This camp is at Frimley, 3 miles from here, I saw a dozen German prisoners today near here and gave them a cigarette each,” he said.

Frimley, also known as Frith Hill Detention Camp, stood in 40 acres of sandy common above Camberley. It was of a temporary nature, was one of the first outdoor camps in England for German prisoners, and was bisected by a public road. On one side were caged military PoW's, while on the other side were civilian internees. They were German nationals who had been stranded in Britain when the war broke out and were deemed a threat to national security.

The hastily erected camp was patrolled by armed territorials and the inmates were said to have provided a “week-end spectacle for Londoners, eager to see the blond beats for themselves”. Gerald Bliss, the motoring correspondent of the Tatler, said that a visit to the camp was “The very last word nowadays.” In fact, it was a perfect opportunity for a family day out! In September 1914, a reporter from The Times paid a visit to Frith Hill and spoke of the prisoners as, “Uhlans wearing riding breeches and spiked helmets, infantry-men in uniforms of blue-green and sailors in navy blue.” The civilian internees were waiters and 'spies' and others, in the garb in which they were arrested, one with a white waistcoat which he had been wearing at a wedding-party when taken.

“The idea of a concentration camp is excellent.”.

Although J.R. appeared not to be anti-German, his postcard was. It was suggested that Frith Hill was “Where most of the Germans in this country ought to be”. When he posted it in November many German civilians had already been rounded up and J.R. tells us he had seen some of them at Frith Hill. “They seem quite happy and included young lads,” he wrote. Frith Hill Detention Camp was Britain's equivalent of Germany's Ruhleben, though it did not last as long as the latter.